Unlearn These Before You Jump to the Buy-Side

From Sell-Side Research to the Buy-Side: What to Ditch

Most sell-side research associates think they’re ready for the buy-side after a couple of years on the job. Most aren’t. Some will never be.

The skills that make you a solid sell-sider—cranking out earnings with your eyes closed, writing notes with pretty charts, and schmoozing with the C-suite and buy-siders—aren’t the ones the buy-side values most in a junior analyst.

Here are the habits you need to ditch if you actually want to make the jump.

Technical

No lazy models. Model what matters.

For a company with three segments with distinct growth, margin and capital intensity, I’ve seen sell-side models slap a multiple on total EBITDA and call it “valuation.” That’s just bad analysis. You need to break them out.

Build models from scratch

When you build the model yourself, you know exactly what drives it. Sell-side models try to please every type of investor—end up pleasing no one. On the buy-side, you build for your process, your workflow, and your audience. No one else.

When I was on the buy-side, I dreaded when my PM asked me to reverse-engineer a sell-side model. My blood pressure would spike trying to decode hard-coded formulas like: new case starts = prior case starts × (2/6 × 15% × 0.975) If I can’t call the analyst, WTF am I supposed to do with that formula?

Don’t get lazy and use a sell-side model, even one inherited from your own team. You probably don’t know every mechanic because most of the time you didn’t build it from scratch (unless you built the model during initiation), and errors can get baked in for years. If you draw faulty conclusion basing on flawed model, you can’t blame the model builder - it’s your fault for trusting the wrong source.

Stop thinking in straight lines

Most sell-side forecasts just extrapolate the past. The buy-side hunts for inflections and second-order effects—places where the future looks different from the past. Train yourself to think nonlinearly.

Understand what accelerates revenue: new products, new geographies, new distribution channels; pull-forwards (remember what happened to mattresses and RVs during COVID); policy changes; secular trends; moving up-market.

Think NVDA—demand for compute exploding, units selling exponentially, not linearly. Coatue and Whale Rock made billions on S-curves. You won’t impress them with a straight-line forecast.

Don’t turn it into a modeling Olympics

If your boss is known for “detailed modeling” on the sell-side, that won’t fly with a “2–3 things that matter” type fund. Go deep only on the drivers that move the stock. Sell-side often conflates busyness with value. Buy-side values speed to the essence.

All three statements matter

Sell-side lives and dies by EPS beats and misses, so it’s easy to forget: real investors value a business on future free cash flows. Cash flow is king. And in asset-heavy sectors, the balance sheet matters—a lot. Even in asset-light sectors, a bad balance sheet can sneak up on you.

If you’re only thinking about growth and margins because that’s all clients ask about, you’re setting yourself up to get blindsided.1

Think in probabilities, not in one “right” outcome

Sure, some sell-siders tack on a bull/bear case at the end of a note—but they’re often so ridiculous they’re useless. That $5 trillion TAM bull case might get you airtime on Bloomberg TV, but it won’t make you money.

Sell-side sells one neat story about the future—the one you can pitch on TV or feed to equity sales. Buy-siders don’t work that way. They think probabilistically and hunt for asymmetric setups.

Get good at building real risk cases. I care less about the bull case—protect the downside and the rest takes care of itself. A solid bear case shows you know where you can be wrong without blowing up.

Do the basics like a pro investor

Just because your sell-side boss hasn’t read a 10-K cover to cover in years doesn’t mean you shouldn’t. If you’re going to put real money behind an idea, you’d better know exactly what you own.

That means reading the 10-K/Q footnotes, the proxy, and every material 8-K. But it doesn’t stop there—edge comes from doing what the rest of the market doesn’t. You can’t just rely on public filings or expert network transcripts (everyone reads those). Talk to suppliers, customers, former employees.

Be unconventional and creative—not to find MNPI, but to uncover overlooked details that build conviction something’s been missed.

Valuation and target price have to make sense now

We all know the sell-side loves playing catch-up to the stock price. You’ve seen the notes—stock’s up 10%, and suddenly the “valuation change” is, “We’re increasing our target price … by 10%.”

Some analysts, if they’re buy-rated, just set the target ~15% above wherever the stock is trading, then reverse-engineer whatever multiple gets them there. Try that in a buy-side interview and you will be shown the door quickly.

On the buy-side, you have to defend why you’re using a specific multiple and why your estimates differ from consensus. Your target price comes from your estimates × your multiple—not the other way around.

I’ve seen plenty of pitches where the candidate’s whole thesis is multiple expansion—but they have no variant view on the fundamentals. “We agree with consensus, but the market’s mis-pricing the stock.”

One guy pitched me a machinery stock, swore it would go from 12× to 18× P/E “because quality will get recognized.” His earnings estimates? Exactly consensus. That’s just hoping for multiple expansion with no fundamental reason—a low-conviction bet you can’t defend in front of a PM.

When you’re starting out, focus on situations where you believe consensus numbers are wrong and assume the multiple stays the same. If you’re right on the fundamentals, you often get multiple expansion for free.

Starting with “it’ll re-rate just because” is building your pitch on air. Your job isn’t to echo the consensus—it’s to disagree with it in a well-supported way. That’s where the alpha is.

There’s more to it than just relative value investors

On the sell-side, target prices are supposed to be 12-month calls—framed to keep relative-value, fast-money clients happy. That falls apart when you’re pitching to absolute-return investors.

Back in the peak TMT mania, ZIRP days, I worked on IPOs as a sell-side research associate where we slapped on a 15–17× sales multiple and called it a target price. Problem: sales multiples eventually have to cash-flow their way into earnings. If the business never turns a profit, it’s a mirage.

Fast-money clients would say, “Peers are trading at 30× sales, mine’s at 20×—if sales accelerates, it can go to 25×, so it’s cheap.” In reality, everything was overpriced on normalized earnings.

You need to project revenue and margins years out, translate that to earnings, apply a sane multiple (if it’s in hyper-growth mode, market multiple), and see what IRR you get.

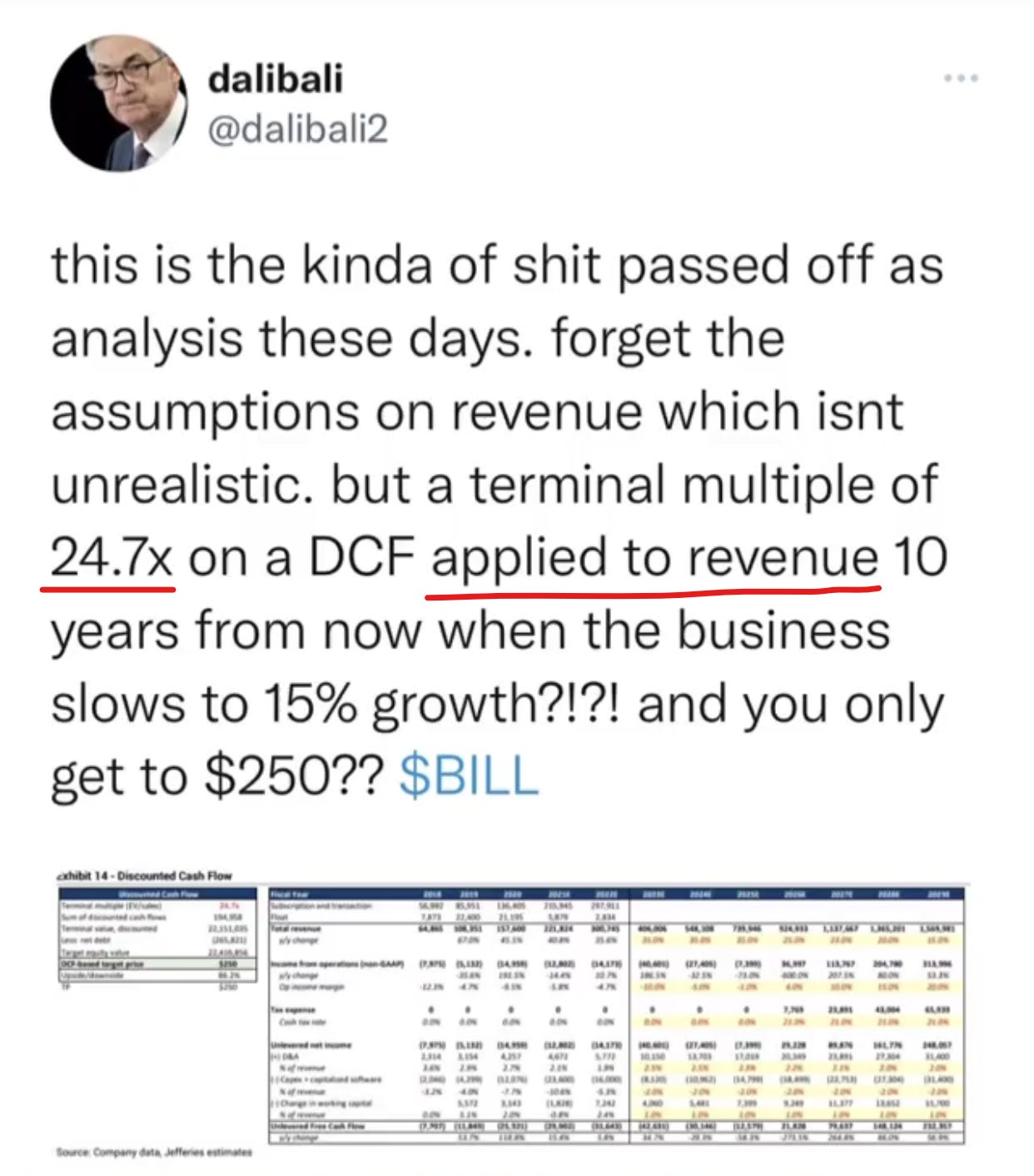

This is why the sell-side gets mocked—you can’t slap a 24.7× SALES exit multiple on a SaaS company and barely catch up to the stock price. If buy-siders can see through it and roast the analyst on Twitter, you’re dead in every buy-side interview pulling the same stunt.

Don’t drink the management Kool-Aid

On the sell-side, too many just repeat management’s story. On the buy-side, your job is to verify. Don’t say, “I think the company can hit $500M in sales in two years because management said so.” Say, “Based on their history of selling 12,000 units a year, I think they can do $480M—so management’s $500M guidance sounds reasonable.”

Remember, IR is paid to spin. Most come from sell-side research—they’re already pros at making a basket of companies sound good, so doing it for one is easy. You can trust them for facts, but never forget the bias: their job is to attract capital, not keep shorts or fast-money traders happy. Management overconfidence is legendary. Validate—don’t just trust.

Your boss’s “channel check” is probably trash

Real alt-data work is a grown-up game with its own skill set. I don’t have it, and the people who do aren’t giving it away—it’s their secret sauce. If you want to weave in alt data in your thesis, please consult a trained professional.

At best, it’s asking some guy your boss knows at a trade show. At worst, it’s something your boss saw on Twitter—or just made up. Don’t build a variant view off that.

Communication

Skip the Hemingway act

Storytelling is great for creators—not stock pitches. The goal is to make money, not grow your readership. That’s why a lot of sell-side analysts get way too fancy with the writing.

I’ve seen pitches that start with, “In the year 1984, the two founders bootstrapped, slept in the office, and mortgaged their house to keep the lights on,” and then the actual thesis was awful. You can’t hide behind a feel-good story when the substance is bad.

Good marketing only works if the product’s solid. In investing, the “product” is your idea—focus on that first.

Keep it tight and actionable

Sell-side loves to fill a page. I’m never sure if it’s because they can’t be concise, or they’re scared a short note looks like they’re slacking. PMs want the so what—not ten pages of stuff they can Google, ask ChatGPT, or call the CEO about.

At my old shop, there was an analyst who’d pump out a note for every press release from his covered companies—sometimes barely rewriting the actual release. I nicknamed him “Captain Obvious.”

Don’t be “Captain Obvious.”

Use first person

On the sell-side, you are told to pitch as “we.” On the buy-side, it’s just you. I learned this the hard way—back when I was an MBA intern, my MD made me restart an entire mock pitch every time I said “I think” instead of “we think.” On the sell-side, the view is the team’s view. That’s just the Wall Street way.

But on the buy-side, you say, “I recommend NVDA as a long.” If you make money, it’s your win. If you lose, it’s your mistake. There’s no “my boss got this one wrong” to hide behind—because now, you’re the boss (of your idea.)

Use confident wording

Take a stance. This is a risk-taking job—you’ll be wrong sometimes, but having no view makes you 100% wrong. Skip the hedges like “could,” “might,” or “optionality.” Say “will” or “is expected to.”

I was taught to open with “I believe” when pitching a stock. Own it.

ELI5

Explain like I'm 5.

Sell-siders get too comfortable talking to sector experts. If you cover software and walk into an interview and say, “This is an open-source, schema-on-read database company,” a generalist PM will be lost.

First, ask yourself if that pitch is even worth it—no extra alpha in complexity. But if you insist, use simple language: open source means anyone can look at the “recipe” for a program, use it, and even change it. Schema-on-read means you put all the data in first, and decide how to sort it later—like tossing all your toys in a box, then figuring out how to group them when you want to play.

If Richard Feynman could make quantum mechanics sound simple, you can make your pitch easy to follow. So know your sh*t and keep it simple.

Drop the sell-side lingo

If it sounds like something you’d write in an earnings note, you need a rewording. “Choppy quarter,” “headline risk,” “solid print,” “beat and raise story,” “clean beat/messy print,” “optionality”—ditch them all.

Use plain English. Instead of “solid print,” say: “Revenue beat by 5% on volume, with no pricing increase.” Instead of “optionality,” say: “If they sell the container management business at 12× EBITDA, that’s 20% upside to the current valuation.” Clear > clever.

Attitude

Know your audience

For most sell-side folks eyeing the buy-side, there’s a big mismatch—the investors you want to work for are often the ones who use the sell-side the least. Instead, you spend your days fielding calls from pod shops you don’t want to join. If you don’t know any better, you start thinking every public investor thinks like a pod shop PM.

You need to know what types of investors are out there, which type you want to be, and who you’re talking to when you network. Are they relative value? Wide moat? Free cash flow/earnings multiple? Most PMs are locked into their style—and they have the bargain power, always. They’re not adapting to you. You adapt to them.

Pitching long-term earnings power story to a relative value shop might work. Pitching “cheap at 20× sales because peers are 30×” to an absolute value shop? Dead on arrival. Tailoring your pitch to your audience can win you big points.

And don’t overlook things you might ignore on the sell-side: liquidity (how easy it is to get in or out), free float (which drives liquidity), and whether the company’s PE-owned (not a dealbreaker, but big PE stakes often mean steady selling pressure).

Do your homework, and your pitch will land stronger.

Have views

The buy-side gets paid to make decisions. Doing nothing doesn’t move P&L. So never—ever—pitch a “hold” to a PM. I made that mistake in my first-ever stock pitch, and I’m just thankful no one chewed me out for it.

If you’re wrong, own it—fast

If your audience was right, check the facts and then actually close the loop. I once told a PM a company’s debt was all fixed-rate. He pushed back. I double-checked that night, and—yep—half was floating. Next day I emailed: “You were right. Here’s the breakdown.” That built more trust than if I’d been right in the first place. That PM is now my good buddy.

Conclusion

You’re doing good work on the sell-side, but moving to the buy-side isn’t as simple—or as transferable—as you think, especially if you haven’t been training yourself like a buy-sider. Spot the gaps now, work on them early, and you’ll be a stronger candidate with a much better shot at landing the seat you want.

Thanks for reading. Please comment below if you have additional insights on your transition from sell-side research to the buy-side.

My tools and insights for navigating public equity recruiting

Check out my other published articles:

📇 Connect with me: Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn | YouTube

If you want to advertise in my newsletter, contact me 👇

If you enjoyed this article, please subscribe and share it with your friends/colleagues. Sharing is what helps us grow! Thank you.

In practice on the buy-side, you can model free cash flow by bridging from the income statement to the cash flow statement without modeling out the full balance sheet, but I’m not going into the nuance here.