Recently, Bill Gurley delivered a talk at the All-In conference that quickly went viral, centering on the pressing issue of regulatory capture. As AI emerges as the next major trend, Gurley's insights are more pertinent than ever. Let’s delve into his perspective and my thoughts.

Definition of Regulatory Capture

Regulatory capture, as defined by Nobel Prize laureate George Stigler, underscores the prevailing tendency where regulations are co-opted by industries and tailored primarily for their own advantage. It is a phenomenon where the interests of specific groups take precedence over the broader interests of the public, ultimately resulting in a net loss for society.

Regulatory capture often occurs through two mechanisms: limiting market entry and ensuring price protection. And money and people influence regulatory capture. Financial contributions, as exemplified by the Citizens United decision, play a pivotal role, but so do the revolving doors that facilitate individuals transitioning between the private sector and regulatory bodies.

I have witnessed the revolving door concept firsthand. When I worked for a large financial institution, some executives had resumes that included experience working for the regulators.

Instead of encouraging free competition, regulations can inadvertently bolster incumbents and further enhance their dominance.

Case Study: Telecom

Bill Gurley's fourth venture capital investment in his career was in a company called Tropos Networks, operating in the WiFi broadband sector. Their mission was to provide free Wi-Fi service in downtown areas, a vision that resonated with hundreds of mayors across the country seeking to enhance public safety, boost economic development, and bridge the digital divide.

However, the entrenched incumbents began flexing their political and financial muscles to protect their interests, leading to a widespread backlash. Lobbyists, acting on behalf of telcos and cable companies like Verizon, Comcast, and later, AT&T, managed to outlaw citywide WiFi initiatives within just two years.

Gurley's discussion highlighted the Telecom Act of 1996, which aimed to promote competition and foster technological progress. However, instead of spurring innovation and investment, it led to the concentration of power in the hands of a few major players and a rapid decline in venture investments in the sector.

This scenario, Gurley argued, mirrored what George Stigler had taught us about how landmark regulatory actions tend to benefit the largest industry players, rather than enhancing competition or customer experiences.

Similarly, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis and the implementation of Dodd-Frank, the largest U.S. banks only grew larger, indicating that regulatory efforts often fall short of their intended objectives.

Case Study: U.S. EHR software

The state of healthcare in the United States has been widely criticized, and Bill Gurley offers compelling case studies to illustrate the issues.

During the Obama administration, a push to encourage the adoption of electronic health records (EHR) software was initiated. Epic Systems, a major private company in Wisconsin, dominated the EHR software market, and the CEO of Epic had close ties to Obama and was appointed as the only corporate representative on the healthcare IT council.

As part of Obama’s American Recovery Act, an agency called ONC1 was created to drive EHR adoption. Under the initiative, each doctor would receive $44,000 if their practice bought EHR software. Furthermore, they would receive an additional $17,000 if they could prove “meaningful use”.

And it gets better: ONC decided that the threshold for meaningful use attestation pretty much mirrors the Epic software feature set. Epic's software became the de facto standard for compliance, enforced by the Department of Justice. Smaller EHR competitors received substantial fines ranging between $57 million to $155 million.

In any industry, a startup typically begins with a simpler product than the incumbent, differentiating on a feature that really matters to the customer, and does it better than the incumbent. Then it adds more features over time. Gurley's point was that ONC regulations acted as a barrier to entry (in his words, “put a brick wall”) for any new players attempting to compete with the entrenched incumbent, Epic.

Case Study: U.S. COVID tests

Gurley provided another more recent example – COVID tests, specifically the rapid antigen tests, which are a very simple technology based on the lateral flow assay. This technology was developed in 1943 and has become a commodity. Interestingly, the packaging is seemingly inconsequential, as you can use the strip without it.

When COVID broke out, Germany heavily leaned into the rapid tests. They evaluated 122 different rapid test vendors and validated 96 of them. As a result, fierce competition arose for a commodity product, ultimately benefiting customers by allowing them to purchase tests for as little as €0.75 each. The U.K. followed suit and produced tests in such abundance and affordability that they were distributed to people's homes for free.

What was happening in the U.S.? Various players in the ecosystem resisted the adoption of rapid tests. Gurley believed that hospitals were reluctant to adopt rapid tests because they were profiting as much from PCR tests as they were from vaccines. Furthermore, only three vendors received approval for selling rapid tests: Abbott, Ellume, and Quidel.

Interestingly, the person at the FDA overseeing the approval of rapid test vendors was Tim Stenzel. And guess where he used to work? Five years as Chief Scientific Officer at Quidel and four years as a Senior Director of Medical, Regulatory, and Clinical Affairs at Abbott.

When President Biden finally embraced antigen tests, the government chose to buy overengineered products from the three approved vendors. Honestly, the U.S. government was probably better off buying tests from the stores in Germany and shipping them to the U.S. Now you know why these tests were so expensive in the US? The lack of open competition for a commodity product.

Case Study: AI

Bill Gurley's concerns about regulation remain incredibly relevant today. He expressed reservations about Sam Altman's proposal for a new regulatory agency to establish standards for AI software before its release, fearing it might lead to Washington exerting excessive control over the software industry, similar to the pharmaceutical sector. Gurley raised the possibility of small AI software startups being required to submit their code for government review and adhere to incumbent-dictated feature mandates (sound familiar?)

Just last week, on October 30, 2023, President Biden issued an executive order highlighting the creation of an AI Safety and Security Advisory Board, which includes industry experts, research labs, critical infrastructure entities, and the U.S. government.

Given Gurley's remarks, he likely views this development cautiously, as it could exacerbate his concerns about excessive regulation potentially stifling AI innovation and competition.

Conclusion

Bill Gurley's frustration with the government's regulatory efforts is evident, as he sees incumbents actively working to hinder potential disruptors. The consequences of ineffective regulation and stifling competition are far-reaching.

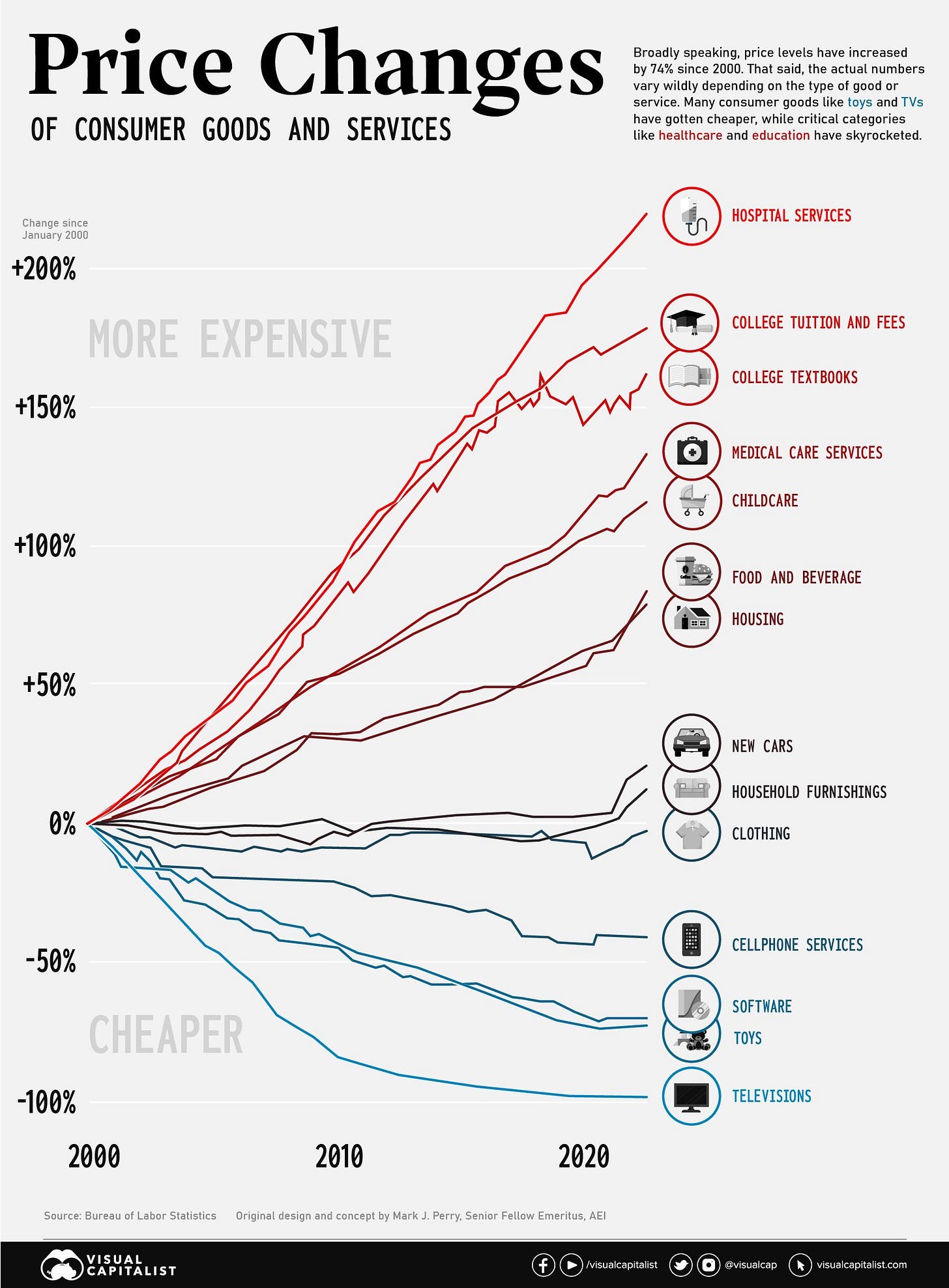

Technology products, driven by intense competition, often face deflationary pressures, benefiting consumers. In contrast, essential services like healthcare and education experience consistent above-inflation price increases, perpetuating inefficiencies and stifling innovation. This trend not only harms consumers but also has broader implications for the country's competitiveness on a global scale.

Gurley proposes several solutions to address these issues, including greater transparency in political contributions, the reevaluation of policies like Citizens United, and increased awareness among voters about their legislators' committee affiliations.

As an investor, you should never underestimate the significance of Michael Porter's "Sixth Force," which Porter refuses to acknowledge as a standalone force and instead argues that government forces merely impact the other five forces.

You just need to recognize that government influences can and often do materially impact the dynamics of competition and business economics. This perspective could enhance the understanding of competitive strategy for students and professionals alike.

Let me know your thoughts in the comments.

Thanks for reading. I will talk to you next time.

If you want to advertise on my newsletter, contact me 👇

Resources for your public equity job search:

Research process and financial modeling (10% off using my code in link)

Check out my other published articles and resources:

📇 Connect with me: Instagram | Twitter | YouTube | LinkedIn

If you enjoyed this article, please subscribe and share it with your friends/colleagues. Sharing is what helps us grow! Thank you.

To watch Bill Gurley’s talk:

Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology

Regulatory moats are incredibly powerful. One of my favorite examples is Verisign $VRSN. I used follow the company much more closely, but EVERY single .com or .net domain is registered through Verisign.

Through an agreement with ICANN, Verisign has the exclusive contract to power the backbone of the internet (the domain name system, DNS). They are capped at charging $8 per domain (with 10% price increases every couple of years) but the lever they pull is increasing the number registrations. VRSN is a master class in the economics of fixed cost leveraging. The company is an absolute cannibal: it buys back somewhere like 5-10% of its stock every year!

And I just checked my notes, last updated late 2021. None other than Berkshire Hathaway owns 12.8m shares, or 11.7%, which makes up 0.78% of their portfolio. This isn't a Buffett investment though. This was bought after Todd joined in the early 2000 teens. And I'm pretty sure Todd has talked publicly about how good of a business VRSN is as well.