Moat GOAT: Otis Elevator

It's a subscription business, what?

Otis Elevator isn’t just a name; it’s a legacy that has redefined vertical transport for over a century. As the inventor of the safety elevator, Otis transformed not only how we move between floors but also how businesses operate in high-rise buildings.

Dive in as we uncover what makes Otis a great business.

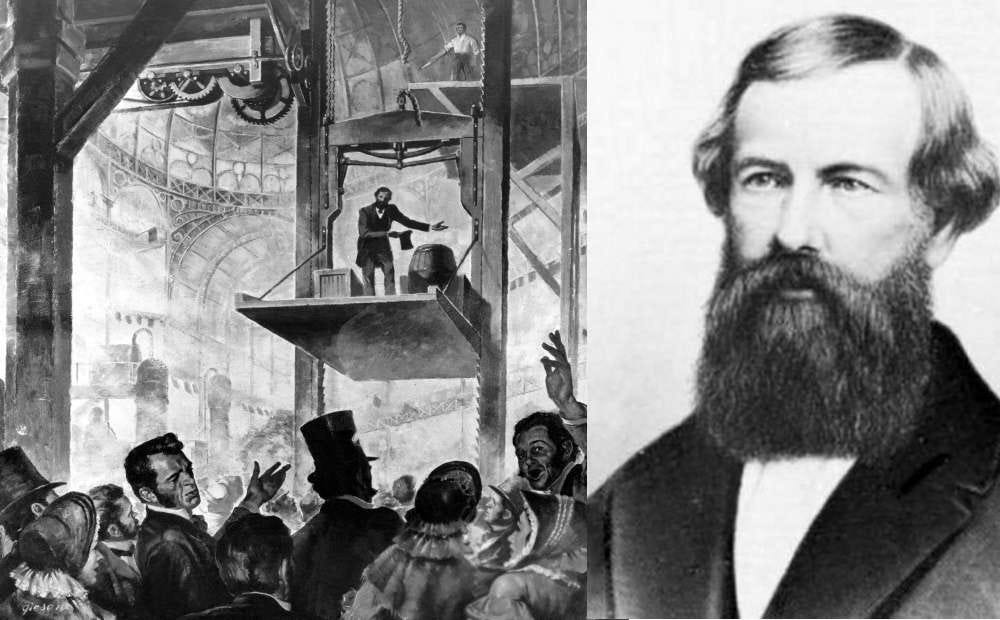

History of Otis

In 1852, Elisha Otis invented the safety elevator, a system that automatically stopped if the hoisting rope failed. His invention captured attention at the 1853 New York World's Fair. When the crowd watched his elevator come to a sudden stop after the rope was intentionally cut, trust was built—and so was the elevator industry.

Otis founded the Otis Elevator Company in 1853 in Yonkers, New York. When he died in 1861, his sons, Charles and Norton, took the reins. During the American Civil War, the demand for Otis elevators surged as they were needed to transport war materials across the U.S. By 1867, the company had grown so much that they opened their first factory in Yonkers.

Fast forward to 1925, and Otis introduced the world’s first fully automatic elevator, Collective Control. Just a few years later, in 1931, the first-ever double-deck elevator was installed at 70 Pine Street in New York City. The company continued to lead the industry with innovations like Autotronic in the 1950s, a computer system that predicted building traffic and optimized elevator deployment, followed by Elevonic in 1977—the first digital, microprocessor-based control system.

Otis was acquired by United Technologies in 1976 and remained under their wing until 2020, when it spun off into an independent company.

The legacy of Otis has reached iconic heights, quite literally. They have installed elevators in some of the world’s tallest and most famous structures, including the Eiffel Tower, the Empire State Building, and the Burj Khalifa. The journey that began with one man's invention has transformed cities, connected people, and elevated the world.

Business Model

What makes Otis a high-ROIC business? It deceptively operates under a high-margin, long-duration subscription revenue model. Otis follows a classic "razor and blade"1 strategy: they attract customers with the sale of lower-margin elevators, but the real value lies in the multi-year maintenance service contracts.

Given that elevators have a usable life of 20-30 years and are difficult to replace once installed during construction, it's easy to see why a company like Otis will do whatever it takes to protect its maintenance revenue base—even if that means selling the elevator itself at a loss.

In 2023, 41% of Otis's sales were tied to new equipment, while 59% came from service, with 82% of that being maintenance and 18% modernization. Service operating profit accounts for 84% of the company's total profit.

The maintenance revenue is effectively recurring due to both product needs (elevators are electronic machinery subject to normal wear and tear) and regulatory requirements (authorities mandate routine maintenance). As you can see, Otis is more resilient than many realize for an industrial machinery company.

Otis serves two different customer bases across its two revenue segments.

New Equipment: Otis sells to real estate developers, building contractors, and general contractors who design and build residential, commercial, retail, and mixed-use buildings. They also sell to government agencies for infrastructure projects such as airports, railways, and metro systems. Elevator installation typically occurs midway through building construction, after the initial structural work is completed. Otis sells new equipment either directly through its sales team or via agents and distributors, depending on the region. The sales team will be a major topic discussed further in this article.

Services (Maintenance and Modernization): Otis serves building owners, facility managers, housing associations, and government agencies—distinct from those involved in purchasing and installing elevators. Large customers prefer working with a scaled player like Otis due to its global coverage and compliance standards. Otis employs 35,000 service mechanics across 1,400 branches in 70 countries.

Customers typically make an advance payment to cover initial design and contract engineering costs, followed by milestone-based payments as installation progresses. New equipment comes with a one-year warranty, after which building owners must purchase maintenance contracts. These upfront payments help Otis on working capital.

Industry structure

The elevator industry is an oligopoly, with the top five players—Otis, Schindler, KONE, ThyssenKrupp, and Mitsubishi—controlling about 70% of the new equipment market (service market is more fragmented). Otis, Schindler, Kone, and ThyssenKrupp are called the "Big 4" due to their dominance in major markets such as the U.S. and Europe, while Mitsubishi is more prominent in Asia.

The elevator industry is highly relationship-driven. A “Big 4” like Otis maintains an edge through global coverage and their relationships with large developers. Developers who choose an OEM for new equipment often continue with the same company for maintenance, making the initial equipment sale a crucial gateway to decades of high-margin maintenance revenue and modernization sales (the latter being an upsell).

In fact, according to an industry expert, 95% of the time, the OEM that installs the elevator also handles the maintenance. The exception is when the building is sold, and the new owner has a maintenance contract with another provider. For example, if a property has an Otis elevator installed but is sold to a REIT who has a national master maintenance agreement with KONE, the REIT will engage KONE for maintenance instead of Otis.

Maintenance service is not optional—local authorities mandate regular servicing. Maintenance contracts are typically multi-year, and many customers renew them as elevators have a 20-30 year usable life. How many software licenses have that kind of longevity? The only two that come to mind are Microsoft and Oracle (both due to high switching costs).

The remaining 30% of the market is served by independent service providers (ISPs), who focus on less complex and lower-$ value maintenance work.

Elevators are interoperable, allowing different OEMs or ISPs to service them.2 However, the Big 4 still secure most of the maintenance contracts due to the relationships built during new equipment sales.

For large customers, disrupting relationships with the Big 4 is challenging, as these companies have nurtured their connections for decades. The mechanics performing elevator repairs are trained by the same labor union, resulting in consistent service quality across the Big 4. Because of this, it's difficult to differentiate based solely on mechanical work; instead, the focus shifts to the intangible relationships.

For large customers, speed of response and customer care are critical. A good service rep is prompt, personable, and capable of influencing mechanics to go the extra mile—even though unionized mechanics typically work 40-hour weeks and may resist overtime, which companies often seek to avoid paying. However, service representatives have sales commissions tied to customer satisfaction, motivating them to ensure smooth operations and to persuade mechanics to deliver exceptional service when necessary.

This commitment to reliable service becomes crucial when issues arise, such as passengers being stuck in an elevator. The need for timely, on-site support globally is why Otis maintains numerous field offices. Their service reps are industry veterans with deep relationships, understanding that once a developer partners with Otis, they are likely to continue using their new equipment and services for future projects.

Adding complexity to the industry are elevator consultants—often former employees of the big OEMs—such as Van Deusen and Lerch Bates. These consultants can influence client buying decisions. Many maintenance service reps stay with one OEM for their entire career, building a loyal book of business and attracting future clients through long-standing relationships with both consultants and customers.

Smaller developers, on the other hand, often turn to ISPs for cost savings, as their maintenance needs are more localized and less complex. This creates a bifurcated market: large developers are served by the "Big 4," while smaller operators rely on independent service providers.

Interestingly, while Otis is tied to the inventor of the elevator, some experts suggest that the quality of actual elevator product has largely reached parity across competitors. The real differentiator is relationships. Customers are also incentivized to stick with the same maintenance provider because they're likely to receive discounts on future installations and maintenance. Additionally, introducing a new maintenance provider for just part of their portfolio introduces operational complexities for the customer.

So in Helmer’s 7 Power Framework, what are Otis moats?

Scale Economics

Only a scaled player like Otis can provide consistent service to large customers across regions. The same advantage also allows Otis to spread fixed costs over a larger base, enabling competitive pricing (and the capacity to take a loss on the new sales just to “land” the customer).

Large developers are unlikely to turn to smaller ISPs, as managing multiple small contracts across regions adds operational complexity. If one independent provider falls short, replacing them can be time-consuming.

Does Otis provide the best service? Probably not, but the consistency globally gives clients that peace of mind similar to why we go to Starbucks (not the best coffee) or McDonalds (definitely not the best burger).

Switching Costs

Once a building has Otis elevators, developers are more likely to continue using Otis for future projects due to the existing relationship. As a result, Otis gets a runway to grow alongside their customers as they take on new projects.

Most developers don’t put their maintenance contracts out to bid unless they've had a truly bad experience, especially since monthly maintenance cost typically represents only a single-digit percentage of the elevator’s installation cost. This explains Otis's 95% attach rate for maintenance contracts following new equipment installations.

It is also more convenient operationally for a developer to have the same company service all the elevators across their property portfolio with a single point of contact (ie. the maintenance sales rep).

Cornered resource

The core advantage of the Big 4 is their ability to employ the best service sales reps who build long-term relationships with large developers, general contractors, and real estate management firms. By taking care of these key clients, the reps establish lifelong relationships, leading to future businesses. This is incredibly difficult to disrupt because the elevator industry is mature and resistant to change. As Helmer might put it, the industry is "hard to counter-position."

Most mechanics in the industry are part of the same union (IUEC) and often move between the Big 4 throughout their careers. Independent service providers (ISPs) typically don’t hire union labor due to the higher costs, which means that repair quality across the Big 4 is largely undifferentiated. Instead, the real difference comes down to customer service—the ability to be responsive and attentive. This is why relationships are the true moat in this industry and the Big 4 own most of these relationships over time.

Additionally, service reps often maintain relationships with elevator consultants, who can influence contract awards. Many of these consultants are former OEM employees, making the industry highly interconnected. As long as Otis and other large OEMs retain top service reps, they will continue winning business from large clients.

Forward growth drivers

Despite holding 70% of the market, there is still an opportunity for Otis and other large OEMs to take share from fragmented independent service providers (ISPs), especially on the service side.

Before the pandemic, modernization was already a growing secular revenue driver, but COVID briefly paused this trend. Globally, 33% of the 16 million installed elevators are over 20 years old, with 60% located in EMEA (Europe, Middle East, and Africa). Otis holds the largest installed base in EMEA, with 1.1 million units, and controls 20% of the region’s modernization sales.

Future growth in modernization is expected to come primarily from China, a fragmented market with over 13,000 ISPs. Larger OEMs like Otis are well-positioned to capture market share from local competitors, especially in service, where scale and expertise offer a significant advantage.

While IoT and AI-enabled elevators have entered the market, I won’t delve into the topic as some experts consider it largely speculative and more of a marketing gimmick at this stage.

Please let me know if you have information on Otis Elevator that I might have missed and/or where I am wrong (as long as you are not being a d*ck.)

If you want to learn about the other moat GOATs I have written about, click this.

Thanks for reading. I will talk to you next time.

Disclaimer: I have no positions in the companies discussed in this article

If you want to advertise on my newsletter, contact me 👇

Resources for your public equity job search:

Research process and financial modeling (10% off using my code in link)

Check out my other published articles and resources:

📇 Connect with me: Instagram | Twitter | YouTube | LinkedIn

If you enjoyed this article, please subscribe and share it with your friends/colleagues. Sharing is what helps us grow! Thank you. 🙏

The "razor and blade" model is named after Gillette’s famous strategy of selling razor handles at little to no margin while making significant profits on the high-margin blades that require frequent replacement. This model has been adopted by many companies, including those in perpetual software, printers, video game consoles, coffee machines, and mobile phones.

Schindler is an exception, with its "closed system," where only Schindler can service the elevator. If a customer switches to Otis as the service provider, Otis lacks the software tools to service a Schindler elevator. This closed system has faced legal challenges but ultimately survived.

Timely piece!