Business Trends in China

My on-the-ground experience

I just got back from a 1.5-month trip in China, spending the majority of my time in my hometown, Shanghai, and taking three separate weeklong trips to Beijing, Chengdu, and Hong Kong. It might be interesting to share an on-the-ground pulse check on business trends there.

Disclaimer: I did not research any of these businesses. All findings are based on my personal interactions with the products or services. If I am wrong, please correct me so we can learn together.

WATCH this article below:

General themes

It’s inconvenient to live life "normally" without a Chinese identity, namely a Chinese ID card, a Chinese bank account and credit card, and a China-made phone.

Fierce competition within different industries is benefiting Chinese consumers for now.

Chinese people are undoubtedly growing wealthier, and more and more international brands want to earn a piece of their wallet share.

Payment

Okay, first things first. I presume the advancement in digital payment in China is well-known among non-Chinese, so let's start here.

You won't need to carry a wallet if you live in China. That said, as discussed in general theme #1, it's inconvenient for a foreigner like me (despite being fully fluent in Mandarin Chinese and Shanghainese, I am no longer a Chinese citizen).

In mainland China, most payment transactions are conducted through either WeChat Pay (Tencent) or Alipay (Alibaba). To be able to use these services, you need the following:

A CHINESE phone number (easy to obtain, buy a prepaid SIM)

An unlocked smartphone (technically easy, but I encountered an unknown "security issue" when my cousin tried to input her credit card information into my WeChat app downloaded from the U.S. iTunes store; AliPay worked fine)

A CHINESE credit card (hard to obtain if you don't live in China; I don't think I can get a Chinese bank account and a credit card on a tourist visa)

Once you overcome the hurdles (my cousin ended up giving me her Xiaomi phone with her phone number and payment information preloaded), the experience of using WeChat Pay and Alipay is great. Either you are scanning the merchant's QR code or the merchant is scanning yours (generated by the app) to pay. Preferably you should have both WeChat Pay and Alipay because some merchants only accept one of the two.

I did not encounter a single merchant accepting credit cards (they do not even have a credit card swipe machine). However, cash is still allowed, probably because of government regulation.

You can even use app-generated QR codes to take buses and the subway. I used Alipay (WeChat Pay has same bus / subway QR code) to take the subway and buses in Shanghai, Beijing, Chengdu, and even Hong Kong, which had its own system for tourists but has seen Alipay enter the market.

I don't know why QR codes are not prevalent in the United States (maybe you know). My conjecture is credit card usage is too deeply entrenched as a habit, making it hard for both merchants and consumers to be receptive to QR codes. Unlike in China, where WeChat has earned its spot as the super app ubiquitous amongst a critical mass of the population, there is no single app dominating in the U.S. Perhaps Apple, by virtue of owning enough share of the total mobile user base, can change that. It's tragic because QR payment is convenient. The danger, while minor, is without cash transactions, it’s easy to lose track of your daily spending. Maybe the Chinese are so used to it.

Phone

You won't survive in China without a smartphone, probably less true in the United States as long as you have a wallet. In China, every ticket you buy is in the form of a QR code authenticated with your ID card. It's a matter of time (or maybe it has already happened) before the Chinese store their ID on the phone as well. All personal and work communications are done on the WeChat app. Email is not big in China, which is why WeChat was able to become the dominant super app. You need your phone at all times.

Similar to Apple, Huawei and Xiaomi have fancy physical stores, their phones are cheaper and functionally equivalent. Some high-end models are even fancier. I don't see how the iPhone can compete in China. Some high-end Xiaomi models even have Leica lenses, a big selling point for photography enthusiasts like me.

The dependence on smartphones is why phone charger rentals are so common. You can easily find Meituan phone power banks (or from another vendor) because you don't want your phone to run out of battery and be unable to use AliPay/WeChat Pay or access your train ticket. It's definitely another unique feature of the Chinese economy.

Retailing

A lot of money is invested in developing mega malls like the ones below in Shanghai, but foot traffic is nonexistent on the floors where only retail stores are located, even on weekends. I don't know how these mega malls (the one below is called shopping park) can survive in the long run knowing how robust e-commerce is in China.

Based on my conversation with my elementary school classmate who works for a global brand, many merchants are cannibalizing their sales by aggressively discounting the same products on digital channels such as T-mall, JD, and Temu. Who would pay full price in physical stores when they know they can get the same product at T-mall for half the price? If merchants are aware of this trend (which I hope they are because numbers don't lie), it's only a matter of time before mall operators suffer as merchants shrink their physical presence.

The benefit for consumers is there are an incredible number of food choices in malls, typically located on the upper floors or in the underground levels, sometimes spanning up to three basement levels of restaurants. During lunchtime, if the mall is part of an office building, it fills up quickly with office workers and, of course, meal delivery workers (I'll discuss meal delivery next time). As a % of an average white-collar worker’s salary, eating out in China is more affordable than in the United States.

Global brands are still incredibly expensive in China, presumably due to import taxes, or perhaps merchants have no idea how to price their products, or the merchants simply think Chinese consumers are gullible. Who in their right mind would pay $60 USD for a North Face t-shirt?

China has experienced such rapid growth that the question moving forward for a tourist like me is, "What gifts exclusively available in China should I bring back to my American friends?" Instead of the past question, "What American brands can't my Chinese friends get in China?" Seriously, they have everything. I'm not talking about KFC, McDonald's, or Pizza Hut, which have been around since I left China 20+ years ago. I'm talking about Peet's Coffee, Tim Hortons, and Shake Shack, as well as luxuries like Loro Piana, Kiton, and Brunello Cucinelli, which I only see in ultra-high-end malls in the United States. The Taikoo Li malls, upscale mall developments in all the cities I visited this time, surpass any mall I've been to in the United States. And I've lived in both New York and San Francisco Bay Area, so I've seen some nice things - can't afford them, but I've seen them.

In the hotel I stayed at in Beijing, there is an Aston Martin dealership in the lobby. I mean, come on, that’s James Bond’s ride! This is a reflection of how much Chinese consumption power has grown over the years. Of course, not all Chinese people can afford an Aston Martin, but at least some people theoretically can afford an Aston Martin for the British to bother setting up a dealership there.

Ride Hailing

Most of you probably know about the botched U.S. IPO of Didi Chuxing (滴滴出行), the Chinese equivalent of Uber/Lyft. However, unless you have traveled to China and can read the language, you probably have never heard of Gaode Map (高德地图). Gaode is kind of like Google Maps (as Google is not usable within mainland China).

Gaode’s main function is searching for locations and figuring out bus/subway routes to get to your destination, but Gaode has the ambition to become another super-app and during this trip, I got to use another feature – ride-hailing aggregation.

Unlike in the United States where ride-hailing is a duopoly between Uber and Lyft, there are many ride-hailing apps (I will use “ride apps” going forward). And Gaode adds value by aggregating them within its app.

I don't know why there are so many ride apps in China. An overabundance of VC money might be the reason. I guarantee some of them will never scale (remember the amount of meal kit companies popped up in the U.S.?) Other than the importance of getting from point A to point B alive (duh), ride-hailing is an undifferentiated service. The abundance of ride-hailing apps has resulted in a price war to gain market share, benefiting customers like me.

Gaode's aggregation has two value-adds:

Aggregating the supply of drivers and the demand of riders. It’s more of a value add to the ride apps, as Chinese riders are unlikely to install more than 2-3 ride apps on their phone, so the smaller apps risk not getting enough riders without the demand aggregation. It’s less of a value add to the riders who can probably find enough drivers using Didi (maybe during peak hour Gaode can help uncover more driver supplies.)

Creating price transparency for consumers.

For these value-adds, Gaode takes a commission, just like any aggregator/marketplace would.

Based on my conversation with a driver, the drivers shoulder Gaode's commission. For example, if a ride costs $20, the ride app takes $8, and Gaode takes an additional $4, leaving the driver with $8.

The economics doesn't make sense to me. Instead, the ride-hailing platform should bear the Gaode commission because attracting riders is more important for the platform than for the driver. Drivers can simply choose to work for another platform (I'm sure many of them "multi-home" on several ride-hailing platforms). As a result of drivers being squeezed twice on each ride, they clearly sound disgruntled, which over time doesn't bode well for the platforms as drivers leave.

Based on my experience, the lesser-known ride apps employ lower-quality drivers (probably by having less strict criteria). For example, one driver was driving 40km/hr on the highway with an 80km/hr speed limit, and a few other drivers have cars reeked of cigarette smell. So, you get what you paid for.

I can imagine Didi has higher-quality drivers and a stricter complaint resolution mechanism, which probably costs riders more. However, consumers are willing to pay for a safer and better experience. Once the industry consolidates, I anticipate Didi (or whoever the long-term winner) can gain pricing power.

I struggle to see how all these ride apps are going to survive in the future. Maybe their capacity to endure is longer than I thought as long as dumb VC money keeps pouring in. Eventually, I anticipate many players will close down for failing to scale into profitability, and then Gaode cannot add value as an aggregator in an eventually duopoly or monopoly Chinese ride-hailing market.

Meal Delivery

Just like in the United States, meal delivery is a staple service in Chinese daily life, especially in big cities like Shanghai. Both meal delivery and ride-hailing make the most sense in high population density areas as essentially hyperlocal logistics businesses. However, compared to ride-hailing, meal delivery creates far more visible social problems in China.

Chinese meal delivery is mostly done on mopeds by these delivery folks (below). As Charlie Munger famously said, "Show me the incentive, and I will show you the outcome." The delivery person gets paid based on the value of orders they deliver, not by the hour. As a result, they are motivated to deliver as quickly and as many orders as they can to maximize earnings.

The outcome is delivery people have no respect for the rule of law on the street. They are ultra-aggressive against other road participants and have no fear for their own life or the lives of pedestrians, car drivers, or anything with a pulse on the street.

I have seen them riding in the wrong direction on one-way streets, never stopping for red lights, and even screaming at other bike riders because the bike riders are in their way. I have heard from the news (stats below) many meal delivery people lost their lives for not following the rules of the road.

They are hardworking people trying to make a living, but I have pretty mixed feelings about the life of Chinese gig workers, to say the least.

China has an enormous population, so the restaurant market is understandably large. As a result, there are so many restaurants and the competition is fierce. Unconfirmed: my cousin told me having meals delivered to you is cheaper than dining in, which is absurd compared to Doordash / UberEats where menu prices are inflated (compared to in-store dining) and all sorts of opaque fees are added to the order (“California fee” and “service fee” come to my mind, maybe they will invent more) that can easily turn $13 burrito order into a $20 bill.

I suspect delivery is cheaper than dine-in in China because restaurants will do anything to sell more items due to the fierce competition and more abundant supply of labor in China.

The Chinese meal delivery industry is a duopoly between the publicly traded Meituan (美团) and Ele.me(饿了么), owned by Alibaba. Their strategies are likely different, as Alibaba can subsidize Ele.me using a cash cow like Alibaba Cloud, while Meituan needs to expand into additional categories (such as groceries, prescription drugs, cosmetics, etc.) to improve unit economics per delivery. The Meituan playbook is similar to that of Doordash.

Similar to ride-hailing, the fierce competition among restaurants and meal delivery platforms is, at least for now, benefiting consumers. For that, as a consumer, I again say “thank you.”

Domestic Traveling

For Chinese citizens, most purchases are linked to their government IDs, which is good for preventing a resale market. For those who don’t have a Chinese ID, it's very inconvenient: The ticketing app/website requires inputting a Chinese government ID number and does not accommodate other forms of identification, such as a foreign passport. Turnstiles at airports, train stations, or tourist spots can only authenticate Chinese IDs. As a non-Chinese citizen, I had to present my passport to a human being who manually verified it in order to enter a tour spot, or take high-speed rail.

The Equity Analyst is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

There are certain hotels that I, as a foreigner, could not stay at because they have not registered with the government and are ineligible to be "internationally facing." This restriction results in foreigners having a smaller supply of hotels compared to locals. I suspect "international facing" hotels have some pricing power. Although I didn't encounter this issue personally, foreigners are prohibited from visiting or staying at some Chinese tourist spots and cities bordering another country for national security reasons.

C-trip (携程旅行)is a dominant OTA (online travel agency) in China. However, Meituan, the meal delivery player discussed in Part 2, is making a push into travel and leisure. I got better-priced travel packages from Meituan’s price competition against C-trip. This is a typical dynamic in the internet business where everyone wants to encroach on each other's territory.

Like its Asian neighbors, China now has an increasingly robust high-speed railway system. The price and efficiency of high-speed rail are starting to threaten domestic airlines. The government is investing to add routes that connect the entire country, especially in Western China with challenging terrains. This investment helps boost domestic consumption and business.

As discussed in Part 1 on the possible overinvestment in physical shopping malls, big money is being poured into developing "water towns" or “old towns” on the outskirts of Shanghai (presumably true for other major Chinese cities as well). I visited a couple of these towns this time: they are very nice.

For example, Panlong Tiandi (蟠龙天地)just opened a few months ago and is owned by the same developer who developed Xintiandi (新天地). These towns are visually appealing, but there might be saturation at a certain point. Chinese people have money and are always looking for the next thing to experience and spend money on, but they also get bored very quickly. It's similar to how, after visiting many European countries, they all start to look the same to me: a town square, outdoor dining, and maybe a canal.

Food Rating

Similar to Yelp, China has an app called "Da Zhong Dian Pin" (roughly translates to “people’s review”, or “DZDP” in short, 大众点评), which is owned by Meituan. It combines features of Yelp, Groupon, meal delivery (the app is owned by Meituan after all), and social media.

As discussed in the meal delivery section, service businesses face fierce competition in China due to the large market and lack of differentiation among restaurants (not easy to differentiate on hot pot, for example - it’s just raw stuff in boiling water/soup). Therefore, having a good rating on DZDP is crucial, as customers are willing to pay more for better food and experience.

DZDP operates similarly to Yelp. I learned DZDP charges RMB 5,000-6,000 (figure unverified, my cousin told me) to "retract" a bad review. Merchants would rather provide goods or services for free in exchange for not receiving a bad review. This practice makes sense economically because redoing a dish costing maybe RMB 500, is preferred over paying 10x to remove a bad review on DZDP.

Electric Vehicles

I definitely was not going to leave out EV when talking about China. Unlike in the US, when the Chinese buy a car, the license plate does not come with it. You need to bid for a license, and it could cost you a fortune. Based on the chart below, a license plate in Shanghai cost a peak of almost 95,000 RMB, or ~$13,000 USD.

However, to encourage the adoption of EVs (with the ulterior motive of providing tangible stimulus to prolong economic "growth"), you get a license plate for free as long as you purchase an EV. The license plate has a different color, and it's not transferable to an ICE vehicle, should you decide to sell the EV.

My cousin drives an Xpeng, and he said charging is basically entirely subsidized by the state utility company, effectively reducing the cost of EV ownership. That's great and all, but with the surge in EV adoption and no barrier to getting a license plate, Chinese roads get more crowded, especially in metro areas, where roads were inadequate to accommodate all the cars on the road before EVs took off. During certain times of the day, congestion is so ridiculous it makes everyone wonder why owning a car in the city is necessary.

Cigarette consumption

Cigarette consumption remains high in China. Rules about smoking in public areas have clearly gotten stricter since I left China, which comforts me as a non-smoker, but it's still not strictly enforced.

The fact that cigarette stores can exist as standalone businesses tells me cigarette consumption remains high enough.

Housing

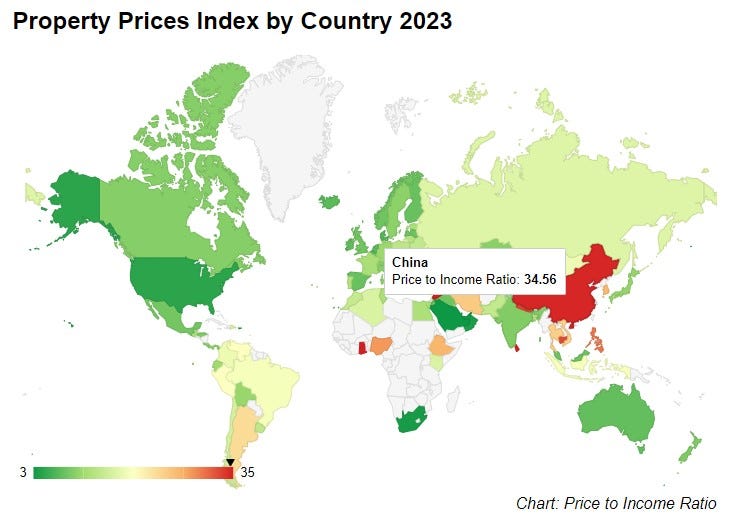

I am saving the best for last. Despite the issues with Evergrande, property prices in major cities, such as Shanghai and Beijing, remain ridiculously high. The price-to-income ratio for housing in China is 35:1 versus the average for the United States is 4.5:1, ie. it costs about 4.5 years of income to afford an average house in the U.S. versus uh … 35 years of income in China.

Chinese citizens are well aware of the oversupply of housing. Despite the oversupply, the prices in the owned market show no signs of coming down. I don't understand, but I suspect the two markets have different dynamics.

To stimulate the economy (I haven't verified this), the government is implementing policies to encourage second-home ownership, especially in tier 2 cities where the economy is likely to slow down more quickly than in tier 1 cities. This is a reversal of the previous policies that discouraged second home ownership to prevent real estate speculation.

High property prices have created serious and prolonged societal problems. There is an oversupply of Chinese men who cannot find a wife because they don't own property, not to mention most of you know there is a growing gender imbalance. The societal expectation that men need to own property (and other tangible assets) before convincing in-laws to marry their daughters remains prevalent.

Many conversations of my parent’s generation revolve around siblings fighting for their parent’s property. You cannot even avoid hearing such conversation when you sit at a coffee shop. It's deeply ingrained in daily Chinese life, to the point where there are even reality TV shows featuring siblings fighting over property inheritance.

I understand incentives drive human behavior, considering the millions, if not tens of millions of RMB worth of cash-generating real estate in Shanghai / Beijing city center is at stake, but it is sad to see people willing to disown their siblings or parents without even blinking for assets and money.

That's all I have on China, leaving it on a sad note. I hope you enjoyed my shallow “fieldwork.” Please comment if you have any questions or insights. I definitely look forward to relaunching this series when I visit China next time.

Thanks for reading. I will talk to you next time.

If you want to advertise on my newsletter, contact me 👇

Resources for your public equity job search:

Research process and financial modeling (10% off using my code in link)

Check out my other published articles and resources:

📇 Connect with me: Instagram | Twitter | YouTube | LinkedIn

If you enjoyed this article, please subscribe and share it with your friends/colleagues. Sharing is what helps us grow! Thank you.