Book Summary - Material World (Part 2)

Part 2: Salt

Recently, I read Ed Conway’s book "Material World", recognized as one of the best books of 2023 by The Economist.

The book opened my eyes to how we often take basic materials for granted, yet underestimate their roles in geopolitics, economics, societal progress, and negative externalities.

The book is divided into discussions on six materials: sand, salt, iron, copper, oil, and lithium. These materials’ significant impact on our lives is underpinned by their abundance and low cost.

Following Part 1 on sand, I will dive into salt in this Part 2.

Salt

Salt plays a crucial role in our life. Before modern refrigerators, salt was the primary method for food preservation. Salting raw foods not only imparted a unique taste but also bought time. Suddenly, a fish caught yesterday didn’t have to be sold today.

Salt is far more significant than most people assume; it was the bedrock for economic trade, the tool of power, and the icon of protest.

Economics

For much of the ancient world, salt was a signifier of wealth.

In the ancient Venetian Empire, the salt office became the heart of its fiscal system, accounting for more than one in seven of every ducat earned by the entire Venetian state.

In China, political creeds from feudalism to communism have come and gone, but throughout Chinese history, the salt monopoly was the one constant. Today the market is still dominated by the state-owned giant China National Salt Industry Corporation (CNSIC); many contend that the CNSIC remains a monopoly in all but name.

In India, the British were able to exert their imperial dominance because India relied on British salt. That’s why Gandhi led a Salt March as a campaign of tax resistance and protest against the British salt monopoly.

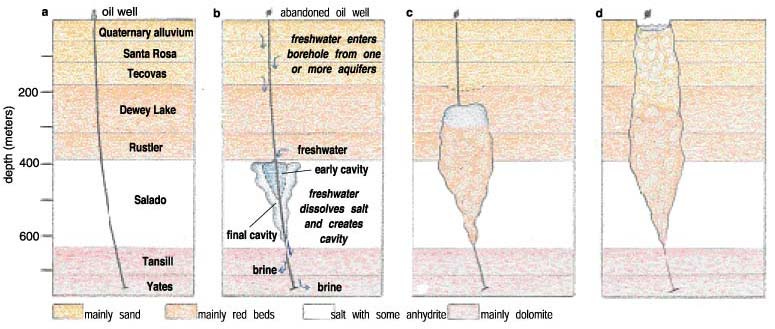

Solution mining is one of the main ways we get salt these days. In the UK, the caverns in early salt mines had too few pillars to hold the roofs, causing frequent collapses. The pumping of brine eroded the rock salt that underlies the country and created sinkholes. In one extreme example, a two-story pub had to make its second floor the new ground floor after the bar fell one floor into the ground.

Inevitably, when the supply of an item grows exponentially, the salt price falls exponentially. Cheshire’s salt producers formed a cartel that would agree on prices and production levels. The experiment was a failure.

Geopolitics

For much of history, those who controlled these substances controlled the world. That’s why one of the first things a country would do before going to war is to stockpile salt.

Saltpeter was often found underground in old cellars and crypts. Mix this salt with a tiny fraction of sulfur and charcoal dust, and you have gunpowder.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the Americans and the Europeans discovered Chincha Islands off the coast of Peru. These are a set of rocks where the birds' droppings from boobies, cormorants, and penguins have accumulated into a crust more than a hundred feet deep. This turned out to be one of the finest natural fertilizers in the world, a combination of phosphate and nitrogen compounds.

A nitrate taxation disruption brought Peru, Bolivia, and Chile into the Nitrate War (Saltpeter War in the book) with Chile winning and gaining control of some of the most important mineral resources in the world, not just the nitrates, but the world’s biggest reserves for copper and lithium. As a result, Chile became the richest nation in Latin America.

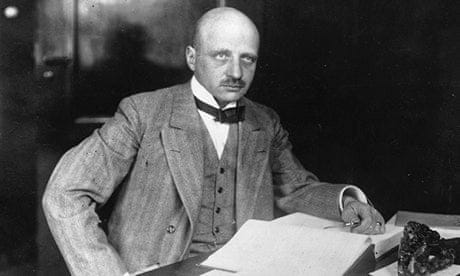

Leading up to World War I, Germany was the world’s biggest importer of Chilean nitrates to use as a fertilizer and an explosive. When World War I broke out, no other country was more exposed. Following a series of battles, Germany was cut off from Chilean mineral deposits for the remainder of the war. With Germany suddenly vulnerable to starvation and, without any source of explosives, catastrophic military defeat, the government looked about desperately for help. They found it in the form of Fritz Haber. He had taken inspiration from how nature did it and tried to simulate lightning, but eventually, he used a combination of heat and pressure to persuade the nitrogen from the air to bond with hydrogen gas. He worked with chemical engineer Carl Bosch to turn a laboratory demonstration into an industrial process.

By 1913, BASF, the company Bosch worked for and eventually led, had begun to manufacture ammonia – that nitrogen/hydrogen compound which could then be converted into fertilizers and used to make explosives. The Haber–Bosch process, as it has become known, is one of the most important scientific and industrial discoveries in history for which Haber won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. It has, in the subsequent century, helped us to feed billions of people.

The Haber–Bosch process delivered a near-fatal blow to Chile’s nitrates industry. Following World War I, Daniel Guggenheim, a member of the famed mining family, pivoted into the nitrate mines in Chile just in time to see it backfire horrendously as the Haber-Bosch process rendered nitrates obsolete. Today, most of the old nitrate outposts have closed.

While nitrogen is by far the most important fertilizer, there are also two others: phosphorus and potassium. Together these three – NPK as they are often called after their chemical symbols – constitute the holy trinity of fertilizers.

For example, potassium owes its name to potash, and potash got its name from the technique used to create it back before the discovery of underground reserves of potassium chloride. Farmers would scrape together the ashes from burned wood, leaching them in a pot, and then evaporating this potash to produce a white salty substance.

The potash industry is an opaque one. Just as there is an oil cartel, OPEC, there is a potash cartel. The Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 created a sudden global shortage of fertilizer since Russia and its ally Belarus provided roughly a quarter of the world’s potash (with Belarus producing 20% of the world’s potash fertilizer alone).

Negative externalities

The recurring theme in the Material World is the negative externalities. Roughly half of the nitrogen scattered and sprayed onto our fields has ended up not in our crops but in our air and water. It has dissolved into streams and rivers, where it has fueled giant algal blooms that suffocate other aquatic life.

Salt as a feedstock

Salt remains the cornerstone of the pharmaceutical and chemical sectors.

The chlor-alkali process stands out as one of the most significant industrial achievements of the modern age. Brine is directed into a room filled with hundreds of electrolysis cells, where a powerful current is passed through it. This process yields chlorine and sodium hydroxide, the latter commonly known as caustic soda.

Caustic soda is often underestimated despite its widespread use in various industrial processes, including the manufacturing of paper, aluminum, soap, and detergents. Many of these items are taken for granted today, but in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, soaps and detergents were considered luxury items.

Even today's pharmaceutical and chemical companies continue to be situated next to salt mines, demonstrating the continued influence of salt in our lives.

Negative externalities

And again, the dark side of the chlor-alkali process is that its products have also been utilized as raw materials for manufacturing chemical weapons.

If you have read the book, what fascinated you about salt that I did not discuss?

I will continue this discussion next time. Thank you for reading.

Check out my other published articles:

If you enjoyed this article, please subscribe and share it with your friends/colleagues. Sharing is what helps us grow! Thank you.