Book Summary - Material World (Part 3)

Part 3: Iron/steel and copper

Recently, I read Ed Conway’s book "Material World", recognized as one of the best books of 2023 by The Economist.

I will dive into iron and copper in Part 3. If you missed Part 1 and Part 2.

Iron/Steel

Iron, a seemingly unassuming element, holds a profound significance in various aspects of our lives. Particularly, its transformation into steel came to define the very essence of modern civilization.

Not everything in the world is made of steel, but nearly everything is made with machines made of steel. For example, John Deere mass-manufactured steel plows. Today Deere is a Fortune 100 company.

To make steel, the iron needs to be separated from the oxygen and a tiny amount of carbon needs to be added. The steel was made ubiquitous thanks to Sir Henry Bessemer’s invention of the Bessemer process that made steel in minutes instead of in hours or days.

Negative Externalities

Steel production is carbon-intensive, responsible for ~7-8% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

The good news is: that in much of the rich world, the demand for iron ore and newly blast-furnaced steel is diminishing because steel is relatively easily recycled. More than two-thirds of America’s steel is now made from scrap.

Ironically, using coal for steelmaking was a solution to environmental problems created by using charcoal. The shortage of timber stocks catalyzed the need for a new fuel source. And people discovered that if they pre-baked the coal, much as you did with wood to make charcoal, they ended up with a purer form of coal with fewer nasty contaminants – coke, as it became known. Since coal was a far more energy-dense fuel than wood, not to mention far more abundant, Britain’s iron production rocketed ahead, prompting a series of other innovations.

Societal Progress

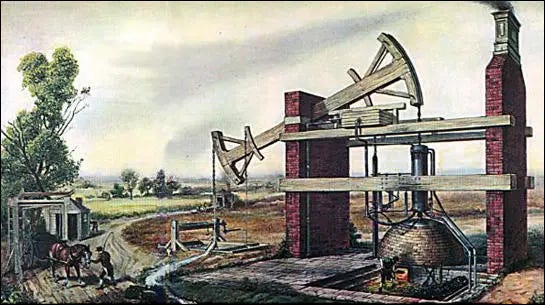

The more coal and iron Britain used, the more it needed to mine, and the deeper it mined, the more work it took to pump water out of the pits. The demand for machines to assist in mining catalyzed the invention of the steam engine.

With the invention of the steam engine, a new use case for coal emerged to power a moving wheel and push a locomotive. Coal and iron were helping to birth the industrial revolution – coal to fuel the machinery, iron to build it, marking the first great energy transition, with humankind shifting from wood and charcoal power to fossil power. No longer was Britain limited by how many trees could be grown on its landmass.

Economics

And the economic implication? By the early nineteenth century, Britain was 80% richer than France.

During different periods of history, steel production has been conflated with a nation’s prosperity because steel is a foundational material used to make machines and factories.

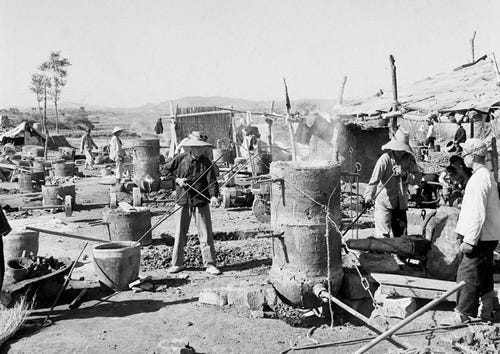

In China, during the Great Leap Forward in the late 1950s, Mao Zedong encouraged families to donate anything iron to make steel and made Citizens build “backyard furnaces” to make steel. Pots and pans, tools and plows were used as raw materials, and homes were torn down so wood would be used as fuel. Iron production was boosted, but not steel because the raw materials were useless iron. Instead of a “leap forward,” China experienced the worst famine in history with a conservative estimate of 17 to 30 million deaths.

Australia has the largest amount of the world’s iron ore reserves. However, this abundance has a dark side: indigenous peoples' lands have been subject to dynamite explosions to clear the way for iron mining.

As consumers, we are complicit in enabling such behavior by major miners in Australia. The availability of cheap Australian iron ore has contributed to China's ability to produce inexpensive goods for the global market, as it is transformed into the steel used in China's factories.

Geopolitics

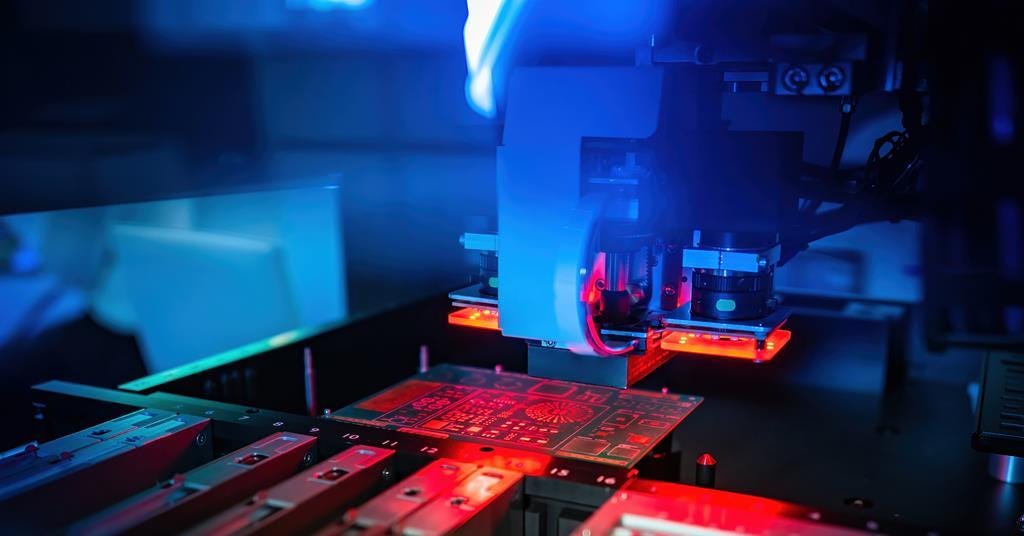

Ukraine became one of the world’s biggest industrial producers of neon as a byproduct of steelmaking. Aside from its more known use in luminescent signs (hence “neon light”), neon is a noble gas used to control the laser wavelengths in photolithography machines in semiconductor manufacturing.

Since Ukrainian steel mills were responsible for producing nearly half the world’s supply of neon, in the weeks after mills shut down because of the war, the world began to run short of neon gas.

When one obscure side product turns out to be essential for another seemingly unrelated supply chain on the other side of the planet, an investor with a deep understanding of second-order effects can profit handsomely.

Copper

Copper is another material we take for granted. Few other metals have the same combination of desirable functions:

heat and electricity conduction

natural ductility: you can roll, pull, and twist into wires without snapping

strength

anti-corrosion nature

recyclability

Take this metal away and much of the electrical infrastructure we rely on is gone.

Just as Thomas Edison did for concrete, he helped turn lightbulbs into a mass-market product. He realized he had to build the electrical infrastructure to power the lights. And that meant a lot of copper: copper to connect the streets of New York and copper to go into homes and workplaces, to string around wheels of the generators. So Edison redesigned the bulbs and his electrical network to not require thick copper and instead use thin ones.

However, one mile out, the power will start to go out. Thankfully, George Westinghouse and Nikola Tesla invented a new trick to solve the problem, alternating currents (AC).

Instead of the constant flow of currents, AC sends pulses of currents which allow high voltages to be sent along very thin wires, which reduces the demand for copper. As a result, people can get electricity despite being too far from a power station.

Societal Progress

For every discovered copper reserve, miners will need to dig further over time to extract the ores as the low-hanging fruits are depleted. As one digs deeper, the ore grades fell: the quantity of stone one needed to move and process to produce a single tonne of copper rose from 50 tonnes to 800 tonnes.

Yet over time, rather than increasing, the inflation-adjusted copper price was essentially flat, driven by human productivity and technological innovation.

During the twentieth century, the number of people working in copper mining and production in the United States fell by two-thirds, but the amount of copper produced more than quadrupled. It is a productivity miracle, just as impressive as Moore’s law for semiconductors.

Additionally, we came up with niftier mining techniques and equipment to extract copper.

Geopolitics

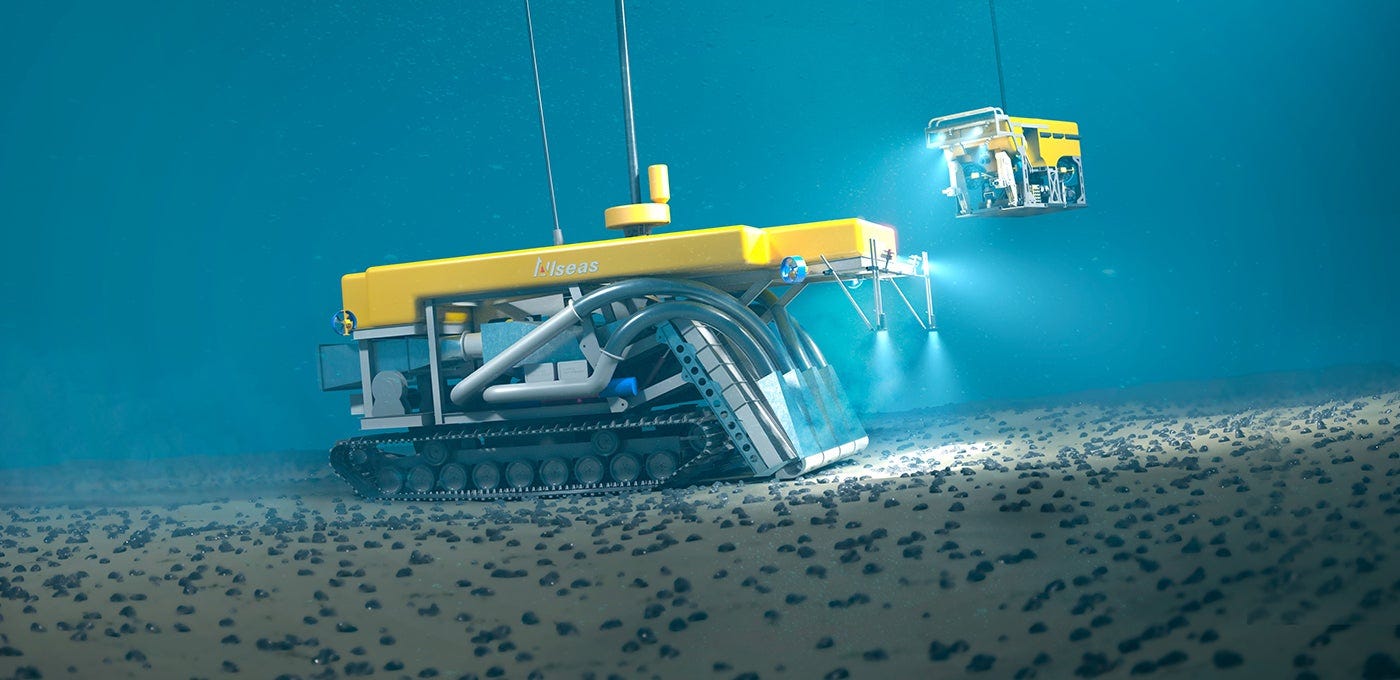

The race for secure commodities such as copper means an unconventional race in the deep seas for resources.

The International Seabed Authority is handing out permits for major nations to mine in the deep sea, creating geopolitical tensions between big nations like China and Russia who have already received permits.

Economics

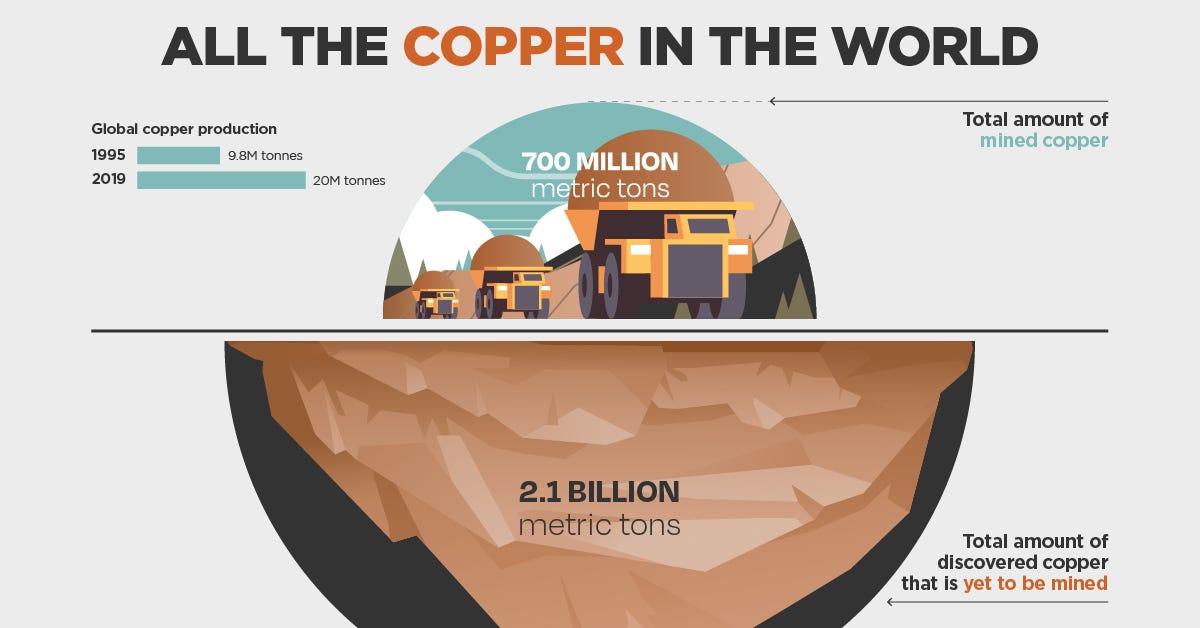

Are we going to run out of copper? No, we are not.

The reason we only have about 30 to 40 years’ worth of copper reserves left is not because that is what’s left in the ground, but because that’s the time horizon over which miners tend to make plans.

Supply growth of copper will comfortably outpace the mining of it. Between 2010 and 2020 we mined 207 million tonnes of copper around the world, but the total global reserves of copper grew by 240 million tonnes.

Between 2020 and 2050 the share of our primary energy coming from electricity is forecast to rise from 20% to 50%. All of a sudden copper becomes the backbone of, well, everything. In electric cars, we need three or four times the amount of copper.

Many have expressed their bullish view on basic materials that are thematically tied to carbon reduction and electrification, as discussed by Eric Mandelblatt of Soroban. The thesis is straightforward: demand for copper is accelerating, while the supply will be slow to come online due to the natural long lead time of copper mines. The risk lies in whether technology will accelerate mining productivity further, thereby reducing unit costs to keep the market price flat.

If you have read the book, what fascinated you about salt that I did not discuss?

I will continue this discussion next time. Thank you for reading.

Check out my other published articles:

If you enjoyed this article, please subscribe and share it with your friends/colleagues. Sharing is what helps us grow! Thank you.