We can’t live without our phones and broadband connections, but have you wondered about how communication infrastructure businesses operate? Let me share with you the history of the U.S. communication infrastructure industry thanks to the trove of wisdom I gathered from Craig Moffett on a Bill Brewster podcast.

If you're interested in listening to the entire podcast, click below:

Regulated monopoly

At the beginning of the 20th century, AT&T T 0.00%↑ was becoming an increasingly dominant monopoly in the U.S. through vertical integration. To settle the antitrust case against the company, AT&T agreed to the Kingsbury Commitment, which included the following provisions:

AT&T agreed to divest itself of the Western Union Telegraph Company (yes, the same Western Union WU 0.00%↑ that does international remittance today).

AT&T allowed independent phone companies to interconnect with its long-distance network.

The government was given the authority to regulate AT&T and turn it into a regulated monopoly.

Government regulation of telecommunications aimed to prevent excessive profits for telecommunications companies and was driven by patriotism. It aimed to establish a stable monopoly in the country's interest that continued until the 1980s.

Deregulation

Legal decisions such as the Carterfone decision allowed innovations such as answering machines, fax machines, and modems to connect to the phone network. The 75-year monopoly started to break down and a new market for customer-premises equipment opened up.1 In the 1980s, MCI and Sprint started to create new competitions in long-distance business servicing enterprises and businesses.

Finally, the Telecom Act of 1996 completely deregulated the telecom market. By that point, long-distance players had been competing for over 10 years, causing the price of long-distance to decrease (as it's considered a commodity, the competition focused on pricing).

Demand for long-distance services was strong, leading to rapid usage growth and the creation of many jobs. The government benefited from this growth through taxes. Therefore, Congress viewed the 10 years of deregulation of long-distance as a positive decision, so they decided to apply the same approach to the local exchange (local telephone company). Unfortunately, the government could not predict that within the next decade, every long-distance company in the U.S. would either be bankrupt or on the verge of bankruptcy.

We have seen this mental model play out in other industries. Howard Marks calls it the “pendulum theory." Moffett pointed out most telecom markets globally have witnessed this pendulum swing between overregulation/regulated monopoly and complete deregulation. And the financial services industry experienced a similar pattern, where the deregulation (of financial derivatives) led to over-speculation, culminating in the 2008 Financial Crisis. In response, politicians proposed regulations to curb excessive risk-taking, leading to tight capital requirements for banks. What ensued is a decade of over-conservatism for banks and too much capital on the balance sheet without being able to be deployed to generate returns for the shareholder and the economy.

How the Cable Industry Started

The backbone of a cable company’s infrastructure is coaxial cable, which became abundant after the Korean War and was easily and cheaply found in local army surplus stores.

Households on the wrong side of a mountain couldn't receive over-the-air antenna television signals from a TV tower. The local electronics stores would then put up a community antenna at the top of the mountain, run the coaxial cable into the valley, and connect it to individual homes, enabling the households to watch TV.

With the development of cable infrastructure, pioneers such as Ted Turner created vast wealth by producing cable-specific TV programming (he created CNN), shaping the industry we know today.

Following the deregulation in 1996, cable companies began competing directly with telephone companies. At that time, many believed telephone companies (today’s AT&T, Verizon, and T-Mobile) would win because they had all the money, established brands, and strong management teams, while cable companies were notorious for their bad customer service and weak balance sheets.

Unfortunately, history proved the consensus wrong: As the internet became mainstream, growing demand for faster internet necessitated an infrastructure that could meet those requirements, and cable infrastructure offered ~4,000 times more capacity than the phone infrastructure, which relied on copper wires primarily built for voice connections (remember DSL broadband?)

As the internet era approached, phone companies found themselves falling behind due to two key reasons.

AT&T had been a monopoly for a long time and did not feel the need to adapt

They suffered from the innovator's dilemma, being torn between catering to their existing phone customers and investing to future proof their business for the internet age.

Misconception About Cable Infra

Cable infrastructure has evolved from pure coax to a hybrid fiber coax (HFC) today, and it has proven to be a resilient model. One common misconception is that cable companies are threatened by pure-play fiber players (whose main product is fiber to the home, “FTTH”), while traditional cable operators have fiber-to-the-node (“FTTN”) architecture, where the last mile from the node to the home uses coaxial cable instead of pure fiber.

According to an expert, when a signal travels across a cable network, 99+% of the time it is traveling on fiber. The short distance of 20 - 30 feet to the home bridged by coaxial cable doesn't make a dramatic difference in this context, making cable and fiber infrastructure functionally identical.

Moffett doesn't believe there is significant consumer demand for a symmetric 10Gbps (ie. 10Gbps download AND upload speed) product. I guess there aren’t that many YouTubers who constantly need to upload large files, though that number is growing every day I assume. Unless there's a surge in demand due to AR/VR applications, he doesn't think the use case (for 10Gbps symmetric) is currently strong enough. This means cable companies have a long runway before running out of capacity.

On Overbuilding

Moffett has been involved in analyzing fiber overbuild for over 30 years in his career. Due to the availability of cheap financing in the last cycle, he foresees that we will soon run out of economically attractive places to build fiber networks.

For cable companies, it is most economically viable to build in high-population-density areas. The key metric is the cost per home passed, and the more homes there are in a given footprint, the more cost-effective it becomes.

However, as more players enter the market, new entrants start to settle for less attractive footprints to overbuild. Currently, projects are being built in the footprint with 4th to 7th decile population density cities, and the projects were initiated when the cost of capital was around 6%. Now, with rising interest rates and increasing labor costs, Moffett anticipates that the bubble will burst, leading to disastrous Internal Rates of Return (IRRs) for the suboptimal overbuild projects. Here comes another mental model and a famous Warren Buffett quote “What the wise do in the beginning, fools do in the end.”

Fixed Mobile Broadband - The Next Frontier

Wireless companies VZ 0.00%↑ , T 0.00%↑, TMUS 0.00%↑ are considered less attractive businesses compared to broadband companies CHTR 0.00%↑ , CMCSA 0.00%↑, ATUS 0.00%↑ because there are fewer broadband players in each market than there are wireless players.

Broadband tends to be more capex intensive upfront and less opex going forward, while wireless has lower capex but higher opex.

Making money in the wireless industry is challenging due to price wars in the current deregulated environment. The wireless market is also saturated and not experiencing significant growth. The wireless companies have approached strategizing for 5G differently.

Verizon is believed to have overpaid $50 billion for C-band Spectrum, which won't generate meaningful incremental revenue anytime soon. Verizon made a strategic mistake by choosing C-band, which faces engineering challenges in propagation and is easily impeded by leaves and raindrops.

Verizon's mistake pales in comparison to AT&T, who went off a tangent to buy DirectTV and Time Warner.

T-Mobile, on the other hand, has an abundance of 2.5GHz spectrums obtained through the Sprint deal. They paid less for the entire Sprint company (Sprint owned the 2.5GHz spectrums) than Verizon paid for the spectrum. Moreover, the 2.5GHz spectrum is seen as a more attractive asset with better propagation and less vulnerable to obstacles.

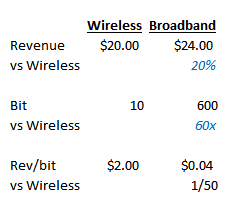

Unfortunately, wireless broadband is not an attractive business due to the economics involved. A broadband household uses 50-70 times more data than a wireless phone subscriber but generates only 20% more revenue. This means that fixed wireless broadband generates 1/50 of the revenue per bit compared to wireless, making it less economically appealing. However, wireless companies have to enter this market to utilize the excess capacity from the acquired spectrum.

Moffett anticipates wireless broadband to be more suitable for rural areas, potentially replacing inferior satellite broadband that previously addressed underserved customer bases where cable infrastructure was absent (because CableCos won’t build in low-density footprints).

Wireless players also face a structural disadvantage due to their financial profiles:

They pay high dividends

They are heavily levered, making it challenging to sustain dividends facing high investment requirements (capex)

AT&T T 0.00%↑ has already cut its dividend. In contrast, T-Mobile TMUS 0.00%↑ , with no legacy of paying dividends, has greater financial flexibility and is better positioned.

While wireless players enter the broadband market, cable companies are entering the wireless market via MVNO (Mobile Virtual Network Operator) arrangements by buying wireless capacity wholesale and reselling it at a fixed margin to their customers. Many dismiss cable companies’ wireless products because of high variable costs2. However, one must remember a wireless network is 90% wired, and cable companies have an infrastructure advantage, leading to cost advantages.

Cable companies initially adopted a hybrid MVNO/WiFi strategy, using wireless player’s capacity but offloading as much traffic as possible onto WiFi. Verizon customers use about 75% of their monthly traffic over WiFi and 25% on the cellular network. In comparison, Comcast sends 90% of traffic over WiFi and 7-8% to the cellular network, resulting in lower marginal costs than Verizon's, defying common perception.

Comcast also outperforms Verizon in most network performance tests since they use Verizon's network coverage wherever it is available but run faster on WiFi due to cable companies' better networks. As a result, cable companies can sell their wireless product cheaper than telcos due to fewer financial obligations, attracting more market share. Furthermore, cable companies are buying cheap unlicensed spectrums and mounting small cells onto telephone poles to offload traffic, keeping some cost savings as profit while passing the rest to lower prices and gain more market share.

The market perceives cable companies' foray into the wireless market as a hobby. In reality, they can become formidable players.

Cable companies have a significant runway since the wireless market is twice as big as the broadband market, although not as profitable, and cable companies have an infrastructure advantage over the incumbent wireless players.

Moffett did not make clear his top CableCo picks, but Altice ATUS 0.00%↑ is clearly not his favorite with self-inflicted issues of increasing prices and cutting costs too quickly. In a rising rate environment for levered companies, the debt doesn’t change, making the equity highly volatile as exhibited in the stock chart below.

Thanks for reading. I will talk to you next time.

If you want to advertise on my newsletter, contact me 👇

Resources for your public equity job search:

Research process and financial modeling (10% off using my code in link)

Check out my other published articles and resources:

📇 Connect with me: Instagram | Twitter | YouTube | LinkedIn

If you enjoyed this article, please subscribe and share it with your friends/colleagues. Sharing is what helps us grow! Thank you.

Before the Carterfone decision, the AT&T monopoly prohibited any non-AT&T equipment to connect to its telephone network. Customers were only limited to using AT&T-approved devices on their telephone lines.

Wireless players gain operation leverage as they gain more subscribers because they own the cell towers. Cable players make fixed profit per subscriber. But it turns out to be a misconception

Great article! Another interesting development within the industry is the rapid adoption of satellite internet connection through Starlink. I interact with remote communities often and have seen the service proliferate virtually everywhere it's offered at surprising speed.