All Things Maverick Capital

How Ainslie founded, built, and operates a large hedge fund

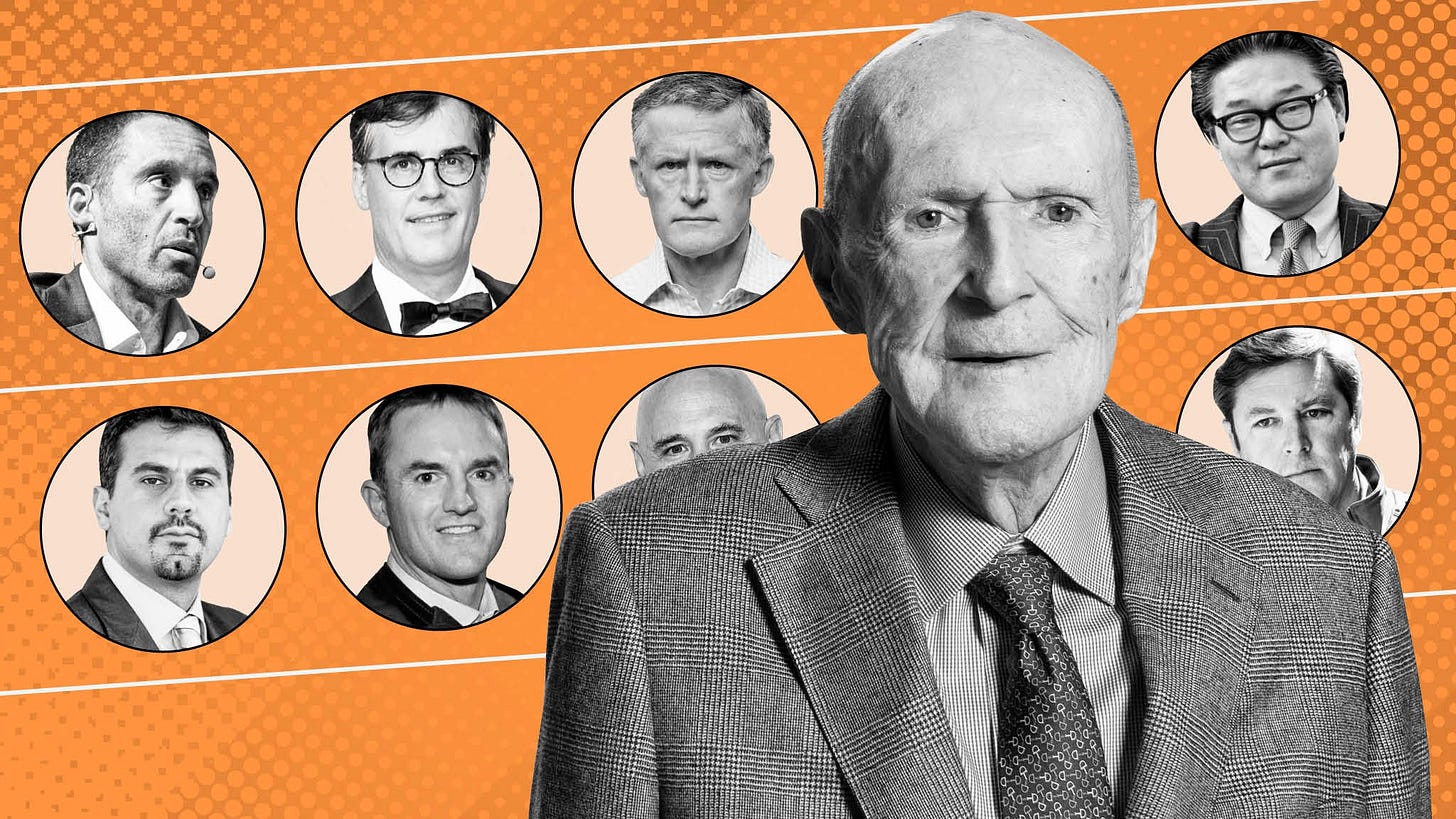

Lee Ainslie is the founder of Maverick Capital, a "Tiger Cub" hedge fund.

In this article, we explore Ainslie's career, the evolution of Maverick Capital under his leadership, and his perspectives on the future direction of the hedge fund industry.

Ainslie received his bachelor’s degree from the University of Virginia and an MBA from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Kenan-Flagler Business School.

As a Junior at Tiger Management

Ainslie's investing journey began under the mentorship of Julian Robertson at Tiger Management.

Interestingly, a pivotal moment in his career came when he was not admitted to Stanford GSB in the late 1980s, which led him to pursue an MBA at the University of North Carolina’s Kenan-Flagler School of Business instead. It was during this time that he was invited to collaborate with the board, a move that later brought Julian Robertson onto the same board.

When Ainslie was initially set to work for Goldman Sachs, Robertson unexpectedly approached him with an offer to join Tiger Management, recognizing his genuine passion for stocks. This decision marked the turning point in Ainslie’s career.

At Tiger, Ainslie closely collaborated with Stephen Mandel (founder of Lone Pine Capital, another successful “Tiger Cub” hedge fund) during his early months, while Mandel already had a distinguished career at Goldman Sachs in equity research.

Ainslie harbored doubts about his first performance review, but to his surprise, not only did he receive a substantial bonus, but he was also entrusted with overseeing the Technology sector, thanks to Mandel's endorsement.

This opportunity was especially significant given the brief tenures of his predecessors as the Head of Technology, and Mandel saw the potential in expanding Lee's responsibilities to benefit Tiger Management.

Finally, in 1993, Lee made the bold decision to leave Tiger Management and establish his own hedge fund, Maverick.

Catalyst to Start Maverick

Julian Robertson was treating Ainslie extremely well, offering both generous compensation and increasing responsibilities. However, Ainslie was approached by Sam Wyly, a serial entrepreneur who saw great potential in the hedge fund business model. Despite Ainslie’s initial reluctance to leave his job at Tiger, Wyly persistently made the idea of departing more appealing.

Ainslie had always harbored the goal of managing his own portfolio, and eventually, he realized that waiting for the perfect moment was unrealistic. The opportunity presented by Wyly was too good to pass up, so Ainslie took the leap, even though he did not fully comprehend the challenges that lay ahead.

Early Challenges at Maverick

When Maverick was founded, there weren't many precedents for starting a hedge fund from scratch. At that time, only one person, David Gerstenhaber, had left Tiger Management to start Argonaut, a macro fund.

Today, it's much easier to set up a hedge fund, with prime brokers providing comprehensive infrastructure support.

Maverick's journey began with $38 million in funding, primarily from the Wyly family. The initial hurdles were significant. Convincing people to meet with them and gaining recognition was challenging. The name "Maverick" didn't help, although Ainslie, at the age of 29, chose it mainly because he was living in Dallas and it sounded appealing. At LP meetings, clients questioned the name Maverick, associating it with impulsiveness.

Ainslie also needed to adjust his investment process. Unlike analysts at Tiger who closely tracked their positions, Ainslie needed a more diversified approach for risk management and track record purposes, which meant relying on friends and sell-side analysts for knowledge, a situation that made him uncomfortable.

Maverick faced a critical year in 1995, and Ainslie knew that if they didn't perform well, the economics of the firm might not make sense, and he would need to find a job in New York.

Fortunately, strong performance in 1995 and 1996 led to asset growth, but it also highlighted the short-term nature of earning investor trust in the hedge fund industry.

Maverick’s Team Structure

Maverick's investment team comprises 29 individuals, with an average of 14 years of investing experience, of which 10 have been within the firm itself.

The team's members have essentially grown up within the Maverick environment, a unique characteristic in an industry where a hedge fund analyst typically works at a fund for an average of two years.

The team is organized into six broad industry sector groups. The six Sector Heads each have on average 21 years of experience, with 16 of those years dedicated to Maverick.

Each sector group consists of 3-6 people, and each investment professional follows 3-5 positions. Most analysts at other hedge funds cover multiples of that amount.

Sector heads are responsible for sourcing long and short ideas globally, but junior analysts are encouraged to bring ideas forward. When familiar with a name, they can swiftly initiate trades, but for new names, a deeper dive is conducted over several months before investment decisions are made.

Maverick employs a stock committee that convenes weekly to evaluate the attractiveness of their holdings and new ideas in the context of the broader market and industry trends. The committee includes the six sector heads, the Chief Risk Officer, and Lee Ainslie himself, with Andrew Warford formerly chairing it before starting his own hedge fund in 2021.

Lastly, Maverick conducts a weekly portfolio management meeting, led by Ainslie, to assess portfolio exposure and risk.

What Does Maverick Look for in Talent?

An investment firm's assets typically boil down to two crucial components: the confidence of its investor base and the talent and dedication of its investment team.

Maverick's inaugural team was assembled from individuals known to Ainslie, a common practice in the hedge fund industry. Naturally, these initial team members had to accept a reduction in compensation.

Most of Maverick's investment team members join as analysts, either after two years on Wall Street or from a consulting background—a unique aspect owing to Ainslie's own experience in management consulting, making him open to such profiles.

Maverick typically extends one or two analyst offers per year, which are often accepted.

A significant emphasis is placed on evaluating emotional consistency, as public market investing has its highs and lows. Being right 55% of the time is considered exceptional, so the ability to handle being wrong and adapt is crucial.

Maverick conducts extensive personality testing, even employing ex-CIA interrogators known as Business Intelligence Analysts (BIA) to enhance interviewing techniques and team management.

Team-oriented performance measurement

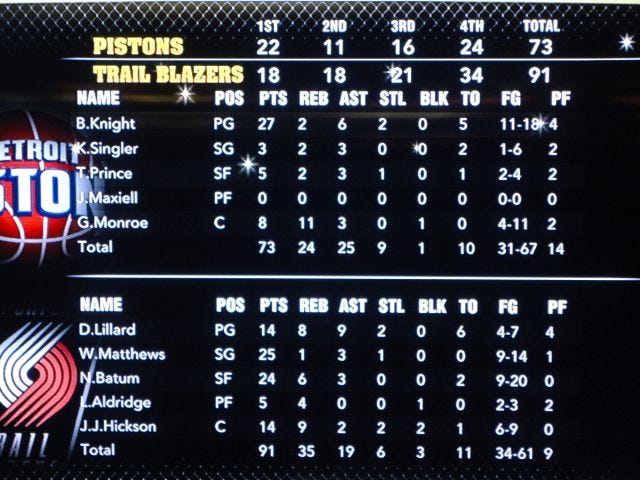

Ainslie is a big fan of basketball and highlights the similarities between the sport and investing in that it emphasizes teamwork with measurable individual contributions. He believes in the power of a highly functioning team, where individual players are willing to make sacrifices for the greater good of the collective. While teamwork is vital, it's equally important that everyone recognizes the true contributors.

Due to a concentrated portfolio and long holding periods, an individual investor at Maverick typically doesn't have a large enough sample set of stocks to evaluate. As a result, Maverick emphasizes teamwork while maintaining a meritocratic approach. The firm keeps track of team-oriented statistics.

Integrity is a core value at Maverick, and the firm does not offer second chances when it comes to statements or conduct that don't align with its ethical standards. In cases of violation, the individual is immediately let go.

Contributing to debates

Ainslie is not looking for talents who agree with everything he says; that doesn't add value. Teams at Maverick engage in constructive debates where members are encouraged to bring different perspectives to the table, challenging ideas.

Juniors are expected to actively generate original ideas from the start. While new analysts may initially support senior team members with modeling, if they have been on the job for six months and haven't contributed a potentially intriguing investment idea, it's a sign that they are on the wrong path. Even if the idea will be shot down, new analysts are encouraged to pitch it.

Given that new hires typically have a surplus of confidence, Maverick hopes their first idea fails so that they are reminded of the challenges of this profession.

Running Maverick

3 jobs of someone running an investment firm:

Stock picking

Constructing and managing the portfolio

Building the business

First Pillar: Stock-picking

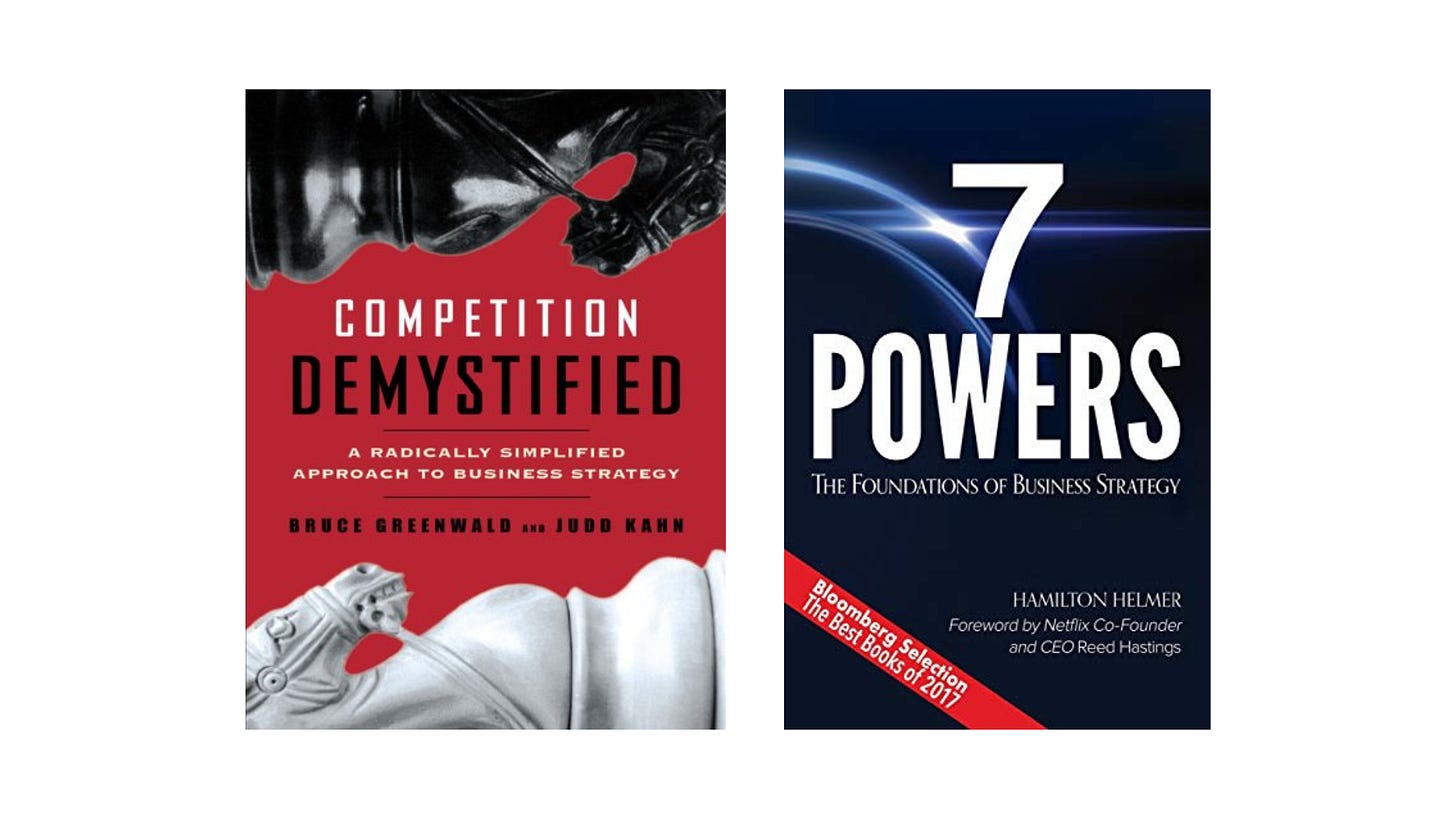

Ainslie's educational and professional journey laid a strong foundation for his investment career. He started with engineering school and later worked as a consultant, primarily focusing on small businesses. These experiences provided valuable insights into diverse business models and the importance of competitive advantages, or "moats," in the business world.

A notable influence on his investment approach was Steve Mandel, who emphasized a deep understanding of individual unit economics.

Back in the early days of Ainslie's career, there was no internet, making access to information a significant advantage.

However, today's landscape is inundated with information, forcing investors to focus on meaningful dialogues with stakeholders like customers, competitors, and suppliers to uncover alpha signals.

Maverick's edge lies in its concentrated sector focus, with junior analysts covering 3-4 names, a ratio that differs from the industry norm.

The average holding period for Maverick's long positions is approximately 17 months, while for shorts, it's around 13 months.

On the long side, Maverick aims to project a business's trajectory 2-3 years ahead, but due to the market's quick recognition of their insights, their holding periods tend to be shorter. For compounders, they "let it run" as long as the reinvestment runway is long and management’s capital allocation remains prudent.

Conversely, on the short side, business flaws become apparent sooner rather than later, leading to more catalyst-driven strategies with higher idea velocity and portfolio turnover.

What does deep dive mean for Maverick?

To ascertain the sustainability of growth and cash flow in businesses, investment professionals at Maverick talk to customers, suppliers, and competitors to deeply understand the strategic positioning and competitive advantages of these businesses.

The firm approaches valuation based on different situations, with the most common method being sustainable free cash flow to enterprise value (FCF yield).

As a hedge fund, the firm places more emphasis on variant perception, preferring non-consensus views.

Maverick spends a lot of time understanding the downside/risk case, which involves debates over assumptions under the downside scenario and the application of trough multiples to understand how low the stock can go should the risk case materialize.

Finally, the firm approaches management evaluation rigorously.

Evaluating Management

The investment team engages with senior executives and managers responsible for regional or product lines, seeking consistency in their responses among each other. Over time, they also evaluate whether management delivers on what they have previously stated to assess alignment between past responses and decision-making.1

They want to evaluate management across dimensions of intelligence, competitiveness, integrity, and their commitment to creating shareholder value.

In meetings with management, Maverick employs techniques akin to those used by intelligence agencies to gain deeper insights, similar to how multi-manager investment professionals are trained.

Additionally, they conduct reference checks, reaching out to individuals who have worked with or competed against the management team members.

While they recognize that management may not be dishonest, Ainslie is aware that managers are often very skilled storytellers who can tell investors what they want to hear.

Employing these techniques ensures unbiased evaluation based on external triangulation rather than taking what management says at face value, which could lead to subpar investment performance.

Quant

At Maverick, quantitative analysis is integral to every step of the investment process.

When analysts delve into research on a particular company, they are required to input detailed models encompassing income statements, cash flow, and balance sheets, all of which must adhere to specific formatting standards.

These inputted financials are then subjected to rigorous scrutiny against historical data, with a focus on understanding any assumptions that deviate from historical norms. While outliers are often where variant perceptions can be developed, this approach is essential.

This meticulous approach relies on strong retention within Maverick's investment team, as lateral hires from other investment firms might find it challenging to appreciate the value of such a structured process that can be viewed as cumbersome.

Alternative Data

Maverick has leveraged its quant team to develop alternative data capabilities. In the past, they have hired individuals to manually count cars in parking lots, but today, they leverage satellite imagery to achieve the same goal.

Ainslie talked about the importance of not being at an informational disadvantage compared to other public investors.

Maverick now maintains a dedicated team focused on extracting alpha signals from key performance indicators (KPIs) using this alternative data. While it's not a perfect system and its effectiveness varies across industries, it provides valuable insights into different trends, ultimately giving the firm a slight edge.

In the world of investing, every incremental improvement in your approach can make a difference in improving your odds of success.

Second Pillar: Portfolio Management

Maverick employs a strategy referred to as the "fresh sheet of paper exercise," which involves envisioning how they would allocate capital if they were starting from scratch, essentially creating an ideal portfolio.

If the new portfolio is indeed their preference, they will transition to the new portfolio.

Maverick has experienced their portfolio going sideways as a result of unexpected market events in the past (Ainslie mentioned the 2011 U.S. treasury downgrade as an example). This led Maverick to improve its quantitative portfolio management system, allowing for more sophistication.

Ainslie is aware of the limitations of a purely quantitative approach, as it often fails to account for forward-looking factors such as changes in secular trends, shifts in strategic positioning, or the impact of new management teams.

While their quant system provides recommended position sizes based on fundamental and off-the-shelf factors, the final decision rests with human judgment.

On average, long positions are roughly twice the size of short positions, and their net long exposure typically falls within the range of 30-60%.

Position sizes for riskier shorts are kept smaller, following standard practices in long/short fund management.

Pillar Three: Running the Hedge Fund

Maverick once contemplated expanding into other asset classes, such as credit and currency. However, a quote from Sol Price about the "intelligent loss of business" sparked a realization – Maverick's true strength lies in stock selection, and venturing into other domains might dilute that expertise.

When asked about what it takes to start a successful fund today, Ainslie emphasized the need for "escape velocity," with firms requiring a minimum of $100 million, if not closer to $250 million, to even secure meetings with LPs, regardless of their performance. What wasn't mentioned is the increasing compliance cost, which can range from $200,000 to $500,000, for starting a hedge fund today.

Solid risk-adjusted returns alone are insufficient; to stand out, one must be willing to take substantial risks and deliver eye-popping results over several years.

Ainslie acknowledged that the odds of success are now more challenging than in the past and stressed the importance of maintaining integrity and fulfilling commitments, as second chances in this competitive arena are hard to come by.

Maverick’s Edge with a Private Investing Arm

Ainslie touts Maverick’s private investing arm as one of its competitive advantages.

The firm started investing capital from its public vehicle in private companies dating back to 1994 (a similar approach that has led Tiger Global on a dramatically different path forward; learn more in this article).

By 2004, the success in this area prompted the creation of a separate entity, Maverick Ventures, to focus specifically on private investments.

The private / public approach allowed for valuable dialogues that influenced Maverick's perspective on disruption and secular trends with substantial impacts on public companies.

For instance, early insights from Sam Altman provided Maverick with an early look at ChatGPT, leading to conclusions about the importance of GPUs.

Drawing from lessons learned in the mobile industry, particularly around the iPhone, Maverick anticipated a supply-demand mismatch for GPUs and began considering its implications for public investments, particularly in companies like Nvidia.

Maverick's informational edge is underpinned by personal relationships, especially in regions like San Francisco, which is attracting twice as much venture capital as the rest of the country combined, even before considering the explosion of AI-related start-ups.

When debating between the success of software stocks versus semiconductors, Ainslie noted that while the number of semiconductor companies with over a $1 billion market cap has slightly decreased, their collective market cap and margins have grown fivefold.

The bottleneck in the industry is expected to revolve around Nvidia chips and other forms of computing power, a trend that even large onshore funds are racing to acquire talent with semiconductor expertise.

Maverick's historical success in recognizing and investing in companies like Nvidia is attributed to their decades of knowledge and experience.

Ainslie acknowledges the attractive features of software companies, such as low capital intensity and high switching costs, but he expects software companies to face difficulty in maintaining their competitive moats due to AI in the future.

When thinking about whether to invest in a new secular trend such as AI, Maverick currently focuses on peripheral players and secondary effects within the AI ecosystem. This approach draws from historical examples where the stock performance of iPhone component suppliers surpassed the performance of Apple stock itself.

On Compensating Fairly

At Maverick, the focus is on ensuring that team members prioritize the net present value (NPV) of their economic contributions over the next 5 to 10 years.

Acknowledging the human inclination to place greater emphasis on compensation relative to peers rather than their actual value addition, Ainslie recognizes the allure of status and rapid wealth accumulation.

Maverick's approach involves assessing each team's performance metrics over the trailing 1, 3, and 5-year periods, aligning compensation with both team performance and metric outcomes.

Ainslie exemplified this ethos with the story of Steve Kapp, the head of healthcare investment at Maverick, who joined the firm without a formal contract, relying on a handshake agreement that symbolized fairness—a principle Maverick has upheld for over two decades.

I strongly resonate with the NPV analogy. Many aspiring investors blindly pursue a career in multi-managers purely because of “higher compensation” without deeply understanding the high stress, the poor work-life balance, and the low stability within the realm of public investing.

Succession Planning

Lee Ainslie has initiated the succession plan at Maverick by implementing a co-CIO structure, with Ben Silver and David Tycocinski taking the lead in overseeing fundamental efforts.

In this process, Ainslie consulted industry veterans, including Seth Klarman and Stanley Druckenmiller.

Druckenmiller's advice emphasized the importance of granting both responsibility and authority to those in leadership positions. He pointed out that partial decision-making authority can lead to suboptimal outcomes, as those closest to the situation are often best equipped to make informed choices.

Furthermore, withholding significant decision-making power can demotivate the individuals assuming leadership roles, ultimately proving detrimental to the organization.

This insight highlights the importance of fully empowering successors in the succession planning process.

On SM L/S Underperformance

Because Ainslie serves on several investment committees, he has noticed the trend in recent years of a growing aversion to long-short equity strategies. This reluctance has been exacerbated by single manager long/short’s underperformance over the past 12 years, culminating in a particularly challenging year when many funds recorded losses exceeding those of the broader market.

The ease with which criticisms can be directed at prominent funds like Tiger Global only adds to the skepticism surrounding this strategy.

Examining the correlation between the HFRI long-short index and equity markets on a trailing 3-year basis reveals a significant shift. Approximately 25 years ago, this correlation stood at less than 30%, highlighting the strategy's distinctiveness. However, in the present day, this correlation has surged to 70%, reaching a peak of 90% just two years ago. Maverick's portfolio has maintained a low correlation in the teens with the HFRI index.

Many smaller hedge funds have given up on alpha shorts, opting instead to use S&P puts or short futures to establish short exposure, a strategy that does not generate short alpha by definition. Many LPs possess the sophistication to replicate such short exposure themselves.

This increasing correlation suggests that many long-short funds are effectively delivering beta rather than alpha to their investors. This shift raises a pertinent question: Why would investors pay management fees for what essentially amounts to beta exposure?

Investment team profile

After analyzing the profiles of 47 investment team members at Maverick, I noticed a few interesting patterns. At the undergraduate level, Georgetown surprisingly leads the pack with 8 alumni (or current member) represented. It’s followed by Harvard (5), Yale (4), Wharton (3), Princeton (2), Ivey (2), and Notre Dame (2)—the only schools with more than one team member. Maverick’s Chief Operating Officer is a grad of Georgetown’s undergraduate business school (McDonough), so that might be why since all candidates go through screening interview with him.

At the MBA level, Harvard Business School stands out with 7 alumni, followed by Columbia with 3. Based on this, it's likely that Maverick recruits MBA interns directly from Harvard, Columbia, and Wharton (which has 1 representative on the team).

As for professional backgrounds, the most common path into Maverick is investment banking—mainly from Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley—or a combination of IB and private equity (the classic 2+2 track). That said, given Lee Ainslie’s openness to management consulting experience, it's not surprising to see a handful of hires from McKinsey, Bain, and BCG as well. Some team members also come from public investing or sell-side equity research roles.

View on Pod Shops

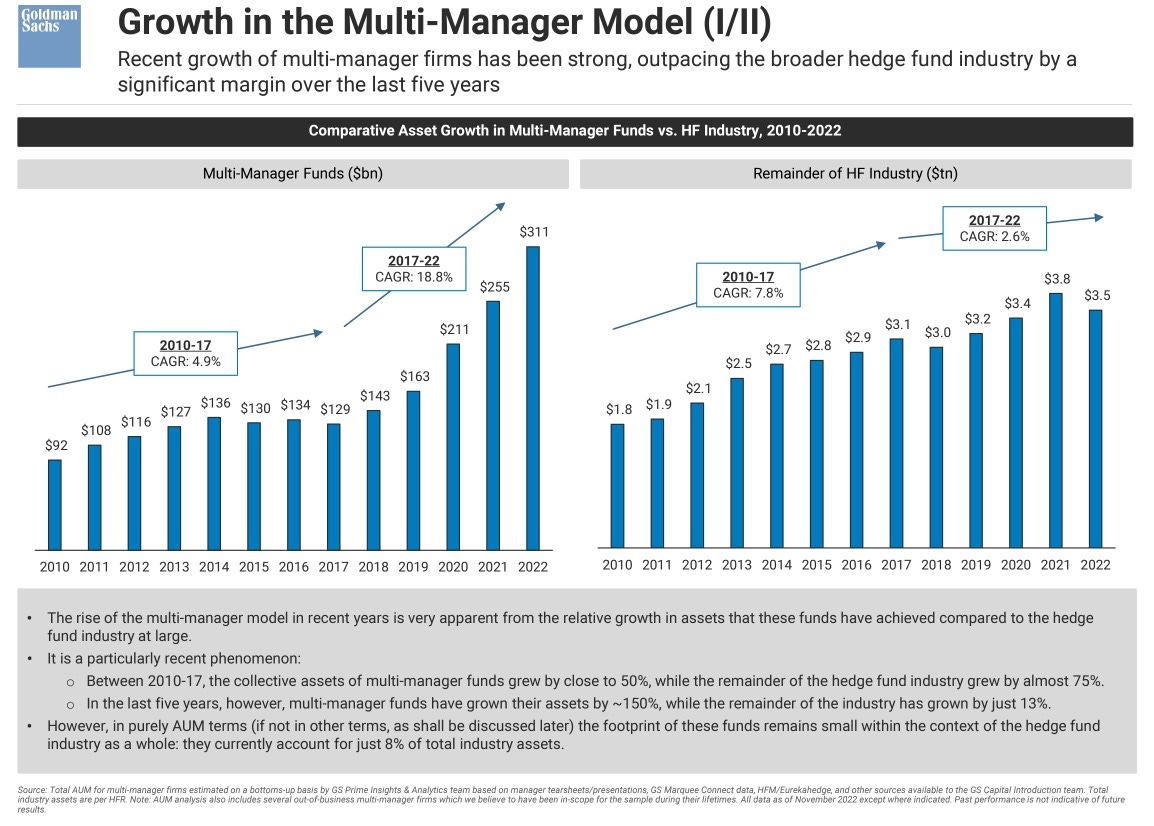

Multi-manager platforms, often referred to as pod shops, have generated a distinctive return profile, diverging from traditional approaches.

However, Ainslie believes that these platforms are going to face increasingly significant challenges in maintaining their performance.

This challenge arises because, when you aggregate the various books within these platforms, you end up with a multitude of positions, both long and short, often simultaneously.

Leverage is undoubtedly a valuable tool, especially in a low-volatility environment, where it can amplify returns. However, as the market transitions into a higher-volatility and higher-cost environment, the implications of leverage shift, potentially increasing risk.

It's also worth noting that these platforms are known for being demanding work environments, and turnover rates tend to be higher compared to other areas of the industry.

Given the evolving market conditions, Ainslie believes that in the next decade, pod shops will face new challenges as they navigate this changing landscape, a view echoed by other market participants, even by Ken Griffin himself.

Outlook for Active Managers

In the face of rising interest rates, Ainslie wants to remind everyone how surprisingly beneficial higher rates are for hedge funds.

Looking at the HFRI long-short index back to 1990, the fed funds rate has been 50-50 in terms of being over 2.5% versus under 2.5%. So it's a good time series to gauge hedge fund value creation. When rates are over 2.5%, on average, hedge funds outperformed the market by 6.5%. Under 2.5%, hedge funds underperformed the market by 4.0%.

This data suggests that higher interest rates create a more productive environment for hedge funds, and the role of short rebates in this equation is relatively minor. The future curve is predicting the market will see fed funds rates between 3.7% to 5.5% in the next 5 years, so it's likely hedge funds will operate in an environment with rates over 2.5%.

When rates are under 2.5%, the equity market returned an average of 9.0%, while when over 2.5%, the equity market returned over 9.7%. So in terms of equity returns, the two worlds don't look too different, so something else must be going on.

The insight lies in the cost of capital for businesses. When two companies are swimming downstream (i.e., in a near-zero cost-of-capital environment), differentiating between companies that are making better decisions becomes challenging because every capital allocation decision appears sound.

However, in a higher-cost capital environment, when the two companies are swimming upstream and both have a 5% cost of capital but one generates a 6% return on capital versus the other generating 14%, the distinction between stronger and weaker companies becomes more evident. That's when active investors can again add value by identifying truly value-creating businesses.

Additionally, borrowing costs for shorts have been at historical lows because many hedge funds have "thrown in the towel" on shorting, which has further benefited funds like Maverick, which still actively shorts and can borrow stocks at costs cheaper than historical norms.

Success of the Tiger Diaspora

Ainslie discussed the remarkable success of numerous managers who had their roots at Tiger Management, including John Griffin of Blue Ridge, Stephen Mandel of Lone Pine, Andreas Halvorsen of Viking, Philippe Laffont of Coatue, and Chase Coleman of Tiger Global, among many others.

Ainslie highlighted Goldman Sachs as the other firm that has produced equally if not more successful investors but is not as recognized because the percentage of hedge fund founders coming out of Tiger Management is much higher due to Tiger’s smaller size.

This trend seemed to underscore Julian Robertson’s eyes for talent. Robertson fostered a collaborative culture where analysts, despite their youth, trusted each other and worked closely together.

Ainslie credited his diverse industry insights to his time at Tiger, where he learned from his peers rather than directly from Robertson.

This strong network continued to support and root for each other, reflecting the non-competitive nature of the hedge fund industry, where even the largest funds hold only tiny market shares.

3 People Ainslie Wants to Have Dinner with

If Ainslie gets a chance to sit down for dinner with three investors, he definitely wants to have Julian Robertson at the table. Robertson's legendary track record and mentorship have been invaluable in shaping Ainslie's investment philosophy.

Another investor Ainslie would love to have dinner with is Warren Buffett. Ainslie has been vocally disagreeing with Buffett's preaching of low portfolio turnover, but Maverick has created alpha through a higher turnover, high transaction cost, low tax efficiency approach. So it just shows there are infinite ways to skin the same cat.

Lastly, Jim Simons would be an intriguing choice. His remarkable achievements in quantitative investing and his dedication to philanthropy make him a fascinating figure in the financial world.

When it comes to company management, Ainslie wants to meet Satya Nadella. His leadership at Microsoft and the strategic pivot towards cloud computing have been truly remarkable, and he would love to gain insights from Satya.

Andy Jassy, CEO of Amazon, is another leader Ainslie admires for his role in shaping the future of cloud computing when he was the head of Amazon Web Services.

And lastly, Ed Breen's reputation for brutal honesty and his ability to turn around companies make him a compelling choice for dinner conversation.

Tech Investing Patterns

As a tech investor, Ainslie emphasizes the need to understand secular trends: where the world is heading and which players are poised to emerge as winners and losers.2

These trends serve as tailwinds. Although investors don't have to rely solely on tailwinds to make money in the stock market, by aligning with secular tailwinds, you can improve your odds of success.

On the other hand, deep-value and traditional value investors who focus on mean reversion don’t rely on tailwinds.

On Tiger Cubs Crowding into Same Stocks

Ainslie denied having frequent conversations with other investors in the Tiger Cub realm.

Tiger Cubs find themselves investing in the same companies because they have a shared interest in identifying high-quality companies.

He believes Tiger Cubs are doing their analyses and reaching their conclusions independently.

Advice to Aspiring Investors

There's no groundbreaking advice here that you haven't already heard.

To build a strong foundation for a career in investing, it's essential to read extensively and immerse yourself in investment books.

Ainslie also wants everyone to note that there are numerous paths to enter the hedge fund world. You don't necessarily have to start your career at a hedge fund or a mutual fund.

In fact, gaining diverse experience in various roles can be highly valuable. Consider working in areas that allow you to gain a deep understanding of different industries or companies, as well as how Wall Street operates.

Opportunities in sell-side research, investment banking, or management consulting at firms like McKinsey can provide you with valuable insights and skills that will serve you well in the investment world. These experiences can offer unique perspectives and knowledge that will set you apart in your career.

Thanks for reading. I will talk to you next time.

Resources for your public equity job search:

Research process and financial modeling (10% off using my code in link)

📇 Connect with me: Instagram | Twitter | YouTube | LinkedIn

If you enjoyed this article, please subscribe and share it with your friends/colleagues. Sharing is what helps us grow! Thank you.

Sources: 1) Podcast with Patrick O'Shaughnessy.

2) Interview with Lee Ainslie from 2014 in CSIMA newsletter.

I know Fidelity employs a similar approach where they keep a folder of all the things management has said in the past and then evaluate ex-post whether they have delivered on their promises.

Of course, this leaves out what really matters, which is the "devil in the details" when ascertaining long-term winners and losers and getting the entry price correct.

Great work!