If you enjoy this article, subscribe to receive future articles on investing, business analysis, and finance career advice. Now, let’s dive in.

Let's discuss the exciting world where two seemingly different realms collide: professional investing and professional sports. Now, you might be wondering what these two worlds have in common. Well, stick around, because we're about to uncover the 5 fascinating parallels and surprising connections between the two.

WATCH this article

Hard to Get In

First of all, both pro investing and sports are extremely competitive to get into because there are so few spots, and the financial rewards are huge. Tens of thousands of people aspire to get into professional investing every year, and the labor market is quite efficient. If something is competitive, it's because a lot of people want to get in. You wouldn't expect tens of thousands of people to aspire to work at a DMV, right?

Many of you have probably wondered why hedge fund managers and research analysts make so much money. The reason is that when the firm scales and has more money to manage, it can expand investable universe from small/mid-cap to large-cap. Instead of buying 100,000 shares, they can now buy a million shares. Moreover, a portfolio manager can efficiently manage only a few people, so even with significant asset under management growth, they might not need to hire many more people. This high operating leverage is why it's so lucrative.

Professional sports operate similarly: It's a media business with high operating leverage. A single game can be monetized multiple times after being played just once. As the audience grows, there's no need to significantly increase personnel to capture higher financial value.

So, what does this mean for you? Even the most talented and passionate individuals struggle to secure a spot in both professions. In professional investing and sports, lineage and brand act as signals for talent potential.

In the investing world, firms often look for candidates who have worked at top investment banking and private equity programs as a ticket to the leading hedge funds. This background acts as a signal of potential, and it enhances the investment firm's marketability when they seek to raise money from clients. Investors find comfort in knowing that they are entrusting their money with someone coming from a reputable traditional background. While this might be disheartening, it's a reality of how the world works.

Similarly, in sports, having a resume that includes playing for prestigious college teams like Alabama or USC for NFL or Memphis, Kentucky, or Coach K for college basketball can significantly help your chances.

Another commonality between professional investing and sports is that they expect you to know how to play the game before you get a chance, which leads to my next point.

Prerequisites Are a Must for Entry

If you're already on the buy-side or even in sell-side equity research, how many times have you heard this line from a clueless prospect: 'Oh, I want to go to the buy-side, man.' Too many of you won't make it into the profession because you want the rewards but don't want to deal with the pain.

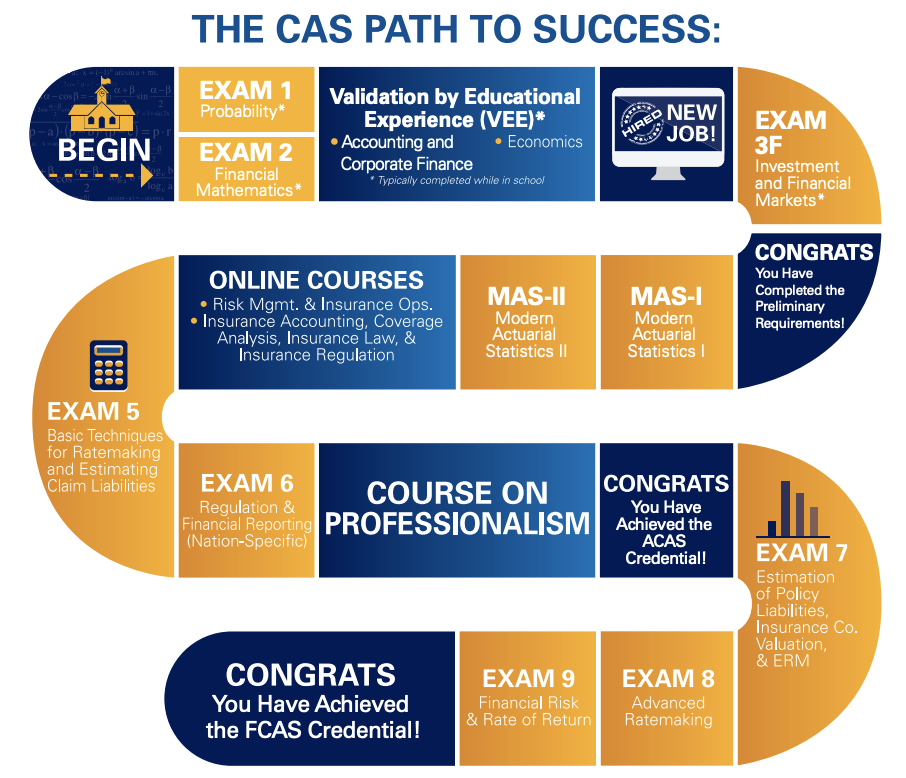

This doesn't just apply to this profession, of course. Let me give you an example from my time as an actuary. A lot of people who reached out to me on LinkedIn told me how much they want to become an actuary because it is intellectually stimulating. When I asked them how many exams they had passed, some of them didn't even know about the gruesome seven to ten years of exams required to get the credential. Some candidates quickly lost interest when they realized the commitment needed, and during informational interviews, they had no meaningful questions to ask. It was frustrating to waste time with such individuals.

Many people want to pursue something without having done their homework. Similarly, in professional investing, everybody wants to find an easy way to do something fancy without knowing what it truly takes. I've been there myself.

Historically, investment firms haven't wanted to train because they can easily hire from investment banking or equity research, which provides a foundational layer of training. However, we all know IB and ER are both grinds in different ways. Buy-siders don't want to train because they prefer to focus on making money. Even for IB and ER candidates, investment firms worry that these candidates might waste their time, which is why they have come up with easy ways to weed out the uncommitted ones. They ask you investing questions, not technical questions—questions about how you think about business and competition. Secondly, they ask for an actionable stock idea and debate it. I cannot think of a better way to assess people because a stock pitch demonstrates both your baseline competence as an investor and your passion for investing.

I understand that many of you may not get into IB or equity research and may feel it's unfair to compete with someone who has developed strong modeling skills or has regular interactions with investors on the job.

Well, no one said life is fair, and the buy-side job search is not fair at all. You can complain about it, or you can get to work. Maybe it's helpful to remind you that investment firms only care about getting the best absolute talent. They don't care if you worked in a back office in a prior life or if you didn't get the necessary training on the job. If there are three candidates—one with direct buy-side experience in the exact investment philosophy, one with Investment Banking experience, and you—whom is the investment firm most likely to hire? The buy-sider who already knows how to do the job.

Thankfully, sometimes you might just be the one to get hired because you read so much, follow the market every day, and have amazing stock ideas. Never count yourself out with the raw hustle it takes to beat out traditional candidates, it's doable. I am an example, and so can you.

In sports, it works in a similar way. For example, many NBA prospects who get drafted were already dominating in college and high school. They already know how to play basketball; the NBA is not going to teach you how to shoot, dribble, or defend. You, as the prospect, need to already know how to do the job. The good news for you is that it's relatively easier to bridge the skill gap for investment management than for professional sports. I have no idea how much work you need to put in to dribble like Kyrie Irving and shoot like Steph Curry.

For those of you who are lucky to have worked in Investment Banking or Equity Research, you already got the training. Show it. If you didn't learn it on your own, no one can do it for you. It won't magically happen. That leads to my next point.

Job Doesn’t End After the Offer

In professional investing and sports, you need to continue doing the job even after you get it. It's trivial, but a lot of people miss that point. Gordon Gekko will say: “Now, you had what it took to get into my office. The real question is whether you have what it takes to stay”

I've worked with candidates who asked me to fudge their current stock pitch so that it comes out looking like a buy thesis, or worse, they asked me to spoon-feed them a pitch. No, not just an idea; they want me to feed them the pitch and the thesis. There are so many problems with these approaches. One, you have to put in your own work. I can't walk into the interview with you to defend the Q&A portion of the interview.

Another issue is that my ideas might not resonate with your style or your audience. In the case of asking me to fudge your pitch into something actionable, you can't milk a dead cow, and you can't change the estimates to make the stocks look cheap. It's intellectually dishonest, and any sensible professional investor will call you out the moment they see it. Most importantly, your interviewer despises intellectual dishonesty because, in this profession, we're not lying to each other; we're playing against the market. The market will tell you that you were wrong, and you will lose money, and that is no joke. The client's money is on the line, and it makes you look really bad.

Of course, these candidates almost always come to me just a day or two before the interview, and that's why they are so desperate. They are asking me to make something magical happen for them so that they get the job. That's another reason why investment firms require a stock pitch because they want to see that you already know how to do the basic work, and even more preferably, you already know what you're doing. Once you start the job, they want you to be able to work independently without constant supervision and guidance.

Contrasting that with the right-minded candidates, they are already doing the buy-side junior analyst's job on their own before they start on the buy side. As for the wrong-minded ones, they spend the majority of their time scheming their way into the profession. Some may slip in by the way, but that is a very dangerous mindset and approach.

Let me give you an example from one of my MBA classmates. She has a similar background to mine, meaning we didn't have any traditional experience in Investment Banking, Private Equity, or Equity Research. She was super determined to get into investment management, and her approach was aggressively cold-emailing hundreds of buy-siders each month without having a stock pitch or understanding her own investment style. She would constantly ask me what are the best questions to ask and how to sound smart in front of her buy-side connections. I told her she was missing the point. I suggested she first figure out her investment style, develop a generally actionable idea, and read a lot so that people know she knows how to do the job and is targeting the right audience. Then, let her talk show how much she knows and how passionate she is about investing. She didn't listen, of course, and she never landed in a buy-side role.

Many of you have the right attitude of being proactive and understanding that this profession is so referral-based. But you forget that you have to be able to do the job even after getting the job. Scheming your way through the interview is the wrong approach because once you're in the profession as a junior, you won't know what your PM will give you to look at. There will be no instruction other than, 'Hey, take a look at this company, and by the end of the week, let me know what you think.'

If you only prepare for how to get the job but not how to do the job, this will be the moment when all your shortcomings are exposed. You might use a borrowed idea and memorize answers to 500 permutations of investing-related questions, but now, you've got the job, and you don't know how to do it. Life is going to be very rough in that buy-side role, my friend, because no one will train you, and you'll have to learn everything on your own. And there's no time, as you must show up to work every day being a useful junior member of the team.

Pro athletes work in the exact same way. They don't train only to nail the combine, which is something they do before they get drafted to showcase their athletic talent and sports acumen. They train to be better athletes and contributors to the team. For example, in the NBA, there are only five players on the court for one team at a time, making it insanely competitive. I doubt anyone trains just to get drafted early, but if they did, I guarantee they didn't get to keep their roster spot for very long and faded away from the league quickly.

For your longevity as a professional investor, why not truly prepare to be a great investor starting today? So that by interview time, the answers come out naturally instead of being rehearsed? I never understand why interviewees come to me and ask how to prepare for the interviews. You don't prepare; it should just show because you've been doing it every day. If you truly claim you love what you are going to do, when someone asks for your investment philosophy, it should just be your investment philosophy, not some canned answers from an investment book or a fund letter. If I were the interviewer, I could easily tell who wants the job versus who wants to succeed in the profession. It's not that hard to tell them apart. So start working on your game today, not after getting the job.

And that leads to my next point: you need to work on your game constantly as an investor.

Non-stop Improvement Is Needed

Investing is not just about doing; you're evaluated on the quality of your recommendation analysis. Doing is merely the input that should lead to quality recommendations, and the harsh reality is it's 100% measurable—either you make money or you don't.

To produce excellent results, just doing the job won't be enough. You need to constantly work on your game on your own. Even then, there is no guarantee you will be a star player because we all have different aptitudes, and some of us may be unlucky to be in a seat where there is a strong misalignment in investment philosophy.

If you ask buy-sider working for a hedge fund or a mutual fund, they will tell you they don't really have a good work-life balance. They don't stop thinking about generating another idea, reading another book, or learning about another business or trend. They are financially motivated to do so. Furthermore, they know that if they don't become a money-making contributor to the team, they will eventually be let go. If you aren't passionate about investing, you'll quickly realize that every day on the job is like the time when you were preparing for buy-side interviews all over again.

Now, do you understand why it's so hard to get a job? It's because it's a test of your commitment to becoming a better and better investor every day for the rest of your life. Most investment firms, towards the end of year two and going into year three, expect you to contribute to making money for the firm with your own ideas. Firms hire you to be analysts, but their goal is for you to become an independent idea generator sooner or later.

The same is true for pro sports. You might get drafted because you're physically talented or thrived in a particular playing system in college, but at the pro level, you'll be competing against the Greek Freak Giannis, who's fast, strong, and ridiculously talented. Or you may have less than a second to throw a football before a 350-pound lineman, who can run a 4.50 40-yard dash, comes at you at full speed. Many of these players just don't last; some aren't as physically dominating at the pro level anymore, their knees gave out, or they suffered multiple concussions and are just out. Others have serious mental issues; they lack work ethic, are arrogant, and un-coachable, leading to their disappearance from the league.

In pro sports, this is similar to being fired. However, look at the superstars like Kobe Bryant, who woke up at 3 AM and trained four times in one day. That's what excellence requires. Many of you want to work at Tiger Cubs, thinking that the founders are great and that it's easy. From my understanding, most of these shops' folks work 80 hours a week. They are great long-term investors and short-term traders, which requires continuous work on their game. You have to be a student of the market every day.

Few True Greats

Another point is that both professional investing and professional sports exhibit power law: there are only that many superstars in these professions.

In the hedge fund land, the chatter is always around Tiger Cubs, Bill Ackman, Dan Loeb, David Tepper, and so on. Every market cycle, there are some random hedge funds that make headlines with some monstrous one-to-three-year track record, but they're never heard from again and vanish in the next cycle.

Hedge fund returns are memoryless; by next January 1st, the scoreboard is wiped clean, and they're back to the grind. So it's really impressive if someone has a track record of putting up strong numbers for 30 years with only a few down years. Those are the very few true legends.

Most of you want to work for those legends only, but that's the problem. Breaking into investment management requires your A-game; breaking into these firms requires a triple-A game. I can't say for sure, but folks at activist firms like Pershing Square and Third Point, work long hours. So, as mentioned previously, a good work-life balance is just a mirage.

Not just long hours, it's more stressful than the long hours you endure in investment banking or equity research because millions or even billions of dollars of client money could be on the line based on a few people's decisions, including yours. So again, do you want to die to go to heaven?

The same is true for sports. As you study the commonality of superstar athletes, they are intense about absolute excellence, not just for themselves but also for their teammates. If you've watched 'The Last Dance,' the documentary about the Chicago Bulls, you know that Michael Jordan was intense not just on himself but also on his teammates. His teammates hated him.

Superstars like Tom Brady, Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant, Tiger Woods, Roger Federer, and Michael Phelps are already naturally gifted. But talent is not enough; you have to outwork your competitors. Races can be decided in milliseconds or one or two points, and these superstars want to be the very best. Not just by talking, they actually are the best because they work harder than even their gifted peers.

The same thing applies to coaches like Bill Belichick, Phil Jackson, and Gregg Popovich. They just put up numbers. Most teams don't win multiple championships in one decade. Phil Jackson has won 11 championships, Gregg Popovich has won five, and Bill Belichick has won eight Super Bowls. Being a superstar has its cost; are you willing to pay the price? If not, that's fine. At least stop saying things without backing them with actions.

Thanks for reading. I will talk to you next time.

If you want to advertise in my newsletter, contact me 👇

Resources for your public equity job search:

Research process and financial modeling (10% off using my code in link)

Check out my other published articles and resources:

📇 Connect with me: Instagram | Twitter | YouTube | LinkedIn

If you enjoyed this article, please subscribe and share it with your friends/colleagues. Sharing is what helps us grow! Thank you.

Brilliant piece. If you put forth the effort, good things will be bestowed upon you.