How to Craft a Winning Stock Pitch

And how NOT to crafting a losing one

I’ve been reviewing a lot of stock pitches lately as part of the job matching initiative. I want to share my take on the do’s and don’ts of stock pitch.

I’ll keep this as a live document, regularly updated, so people can check in and see if they’re improving their stock pitching skills. And it is an area where I can improve in adding more value to my growing audience, because I still don’t understand fully the root of people’s struggle.

Let’s dive in.

What is a stock pitch?

A stock pitch has one goal: getting your audience to take action – buy or short the stock to make money (I’m focusing on the long side here).

The first thing I will read are your theses. So, get straight to the point and highlight what matters. If we have questions, we’ll ask you afterward, and you should know all the details, but don’t give us everything in the pitch.

A stock is publicly traded ownership of a business. The stock price is reflection of:

Financial metric: EPS, EBITDA, free cash flow, etc.

Valuation multiple (“multiple” in future references)

Both financial metrics and the multiple need to be on a forward basis because we are buying into the future of the business, not the present or the past. For example, stock price = NTM P/E * NTM EPS (NTM stands for “next twelve months”)

You make money when the financial metric and/or the multiple goes up in the future. Different investing styles may prioritize financial metric growth or multiple expansion.

Your pitch has to be actionable now, not just a hindsight win from 2022. If the stock’s already up 200% and the upside is gone, it might not be actionable anymore. In that case, find new ideas. Do not fudge numbers to make it look like there’s more upside – people see right through that.

No thesis = no pitch

If you don’t have a real thesis, you don’t have a pitch. Don’t give us a multi-page history of the company - you cannot hide from the lack of substance.

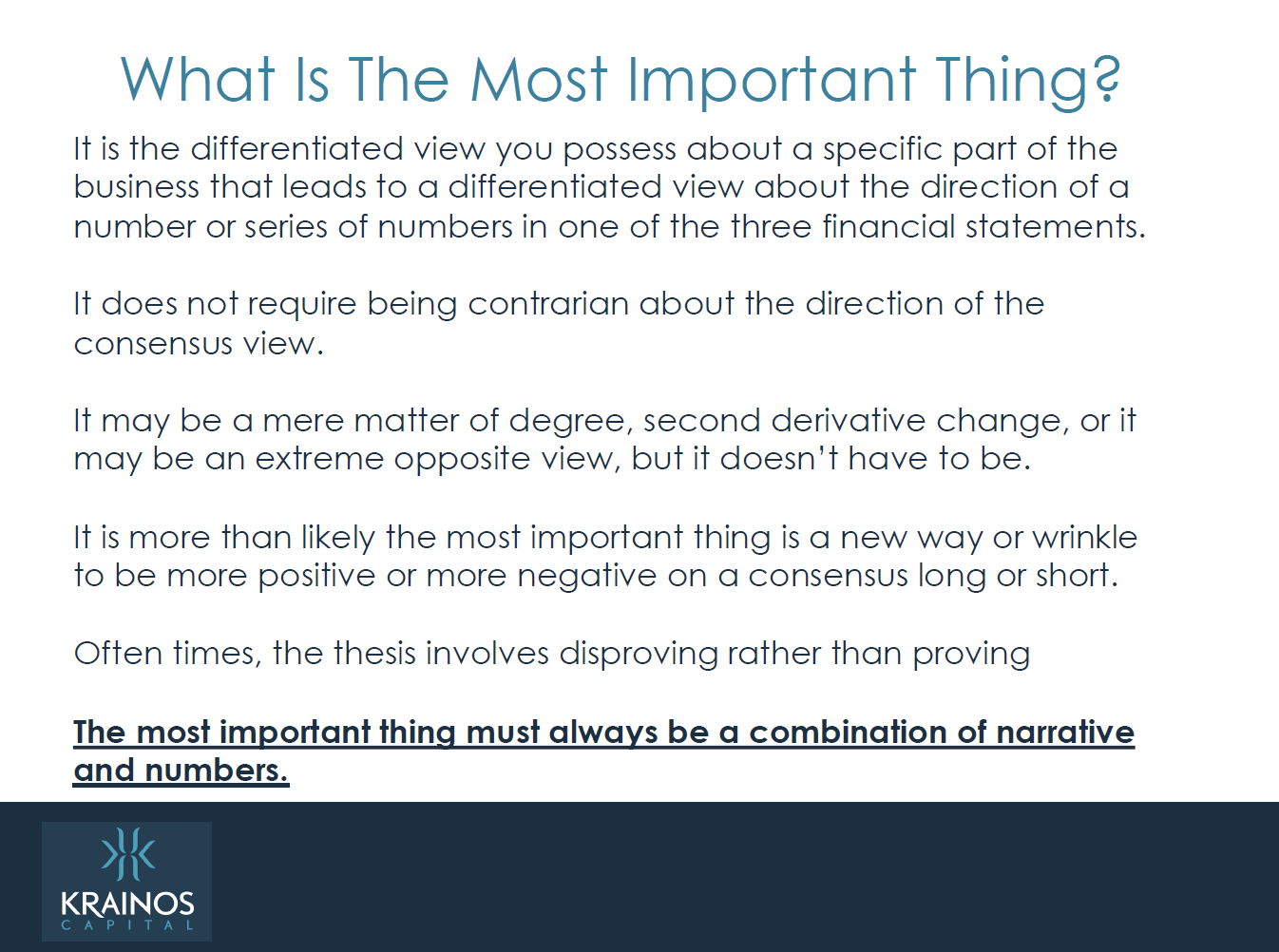

Every thesis should impact future financial metrics—ideally in a way the market doesn’t expect—or affect the multiple. You don’t have to have a near-term variant view, but if your numbers align with consensus, you must defend why the multiple holds up in your forecast period. That could mean the market underestimates the longevity of above-market growth or the company’s ability to compound earnings exponentially.

If you’re new to stock research, focus on the financials and assume the multiple stays the same. It’s easier to justify and, while still challenging, easier to develop views on the numbers. Plus, multiples often expand anyways when your view on the financials turns out to be correctly (ie. higher than the consensus.)

Praising past achievements, like “The company has achieved 20% revenue CAGR or expanded margin by 100bps per year for the past 10 years, therefore it’s a buy,” doesn’t cut it. We’re buying into the future. You need to defend why it can continue to grow or expand margins at the same rate. Most importantly, is it already expected by the market? Often things get interesting because the future is unlike the past (eg. at the start of an S-curve, tail winded businesses experience exponential unit growth, heard of Nvidia?)

AI can easily build a three-statement model, and so can anyone who’s taken a financial modeling course. Assumptions pulled from thin air are easy to spot. If you’re just applying a historical revenue growth rate to forecast the overall company revenue while the company tells you the business drivers (more on that later), you’re not thinking about how the business makes money.

If you forecast 2% revenue growth for five years with a bear case of -2% and a bull case of 6%—numbers that seem plucked from thin air—people will stop reading. No real thesis, no real pitch.

Put in the work to understand the business and the industry and at least come up with assumptions that make sense.

Presenting your pitch

Format? Doesn’t matter. The two common ones are slide decks and write-ups. You won’t always know what your audience wants. I accept both for job matching. If a firm mandates the format, follow them. Otherwise, go with what your preferred way.

If it’s a write-up, keep it under two pages (supplementals can go into an appendix.) If it’s a deck, make it tight—no fluff. There’s no one-size-fits-all best practice. Paul Enright emphasizes balancing story and numbers. Brett Caughran (he likes slides) says to mix pictures and text.

Presentations matter. You’re up against peers in high-intensity professions. Inconsistent fonts in the same model? Sloppy. Charts should be labeled and consistent—bare minimum. But poor formatting is easier to fix than weak theses. If you don’t have real theses, no amount of fancy charts will save you.

Don’t use sell-side note format. Don’t slot your write-up into a generic sell-side research template. And don’t turn in a quarterly earnings recap or initiation report—that’s not a pitch.

It’s sloppy when you repurpose work without even cleaning it up. Leave out the course names, student fund name, CFA competitions, etc.

Learn how to use AI. Use ChatGPT to be more concise without losing substance. Hire a contractor if your visuals need work. There are plenty of guides on how to use AI to better your writing, if you are a self-starter, you will go find them. If you are not, well, you will never get a job in this profession anyways.

Pitch structure

Use this structure as a guide—you don’t have to follow it exactly.

Conclusion up front: I am (don’t say “we”) long TICKER, market cap and price target, and % upside, implied IRR % over what time horizon

How did you get to your price target (multiple of future earnings/EBITDA/FCF, SoTP (sum of the parts), etc.)

What does the company do, how does it make money, what’s the industry structure and how the company fits into the industry?

Summarize the 2-3 theses points on the stocks up front. All theses need to affect the fundamental forecast and/or valuation.

Dive into thesis points and provide evidence of research and numbers to support points – be sure to clearly explain how your view differs from consensus (i.e. the market); Focus most of your energy on fundamentals rather than multiple expansion.

Summarize valuation (including slightly more detail than upfront), and conclude by reiterating your price target and % upside

Include a financial summary and your model

I always share this pitch to my audience because it’s cleanest I have ever seen (the stock didn’t even work out). I rehashed it to be even more concise than it already was. Please note the pitch was written in May 2016.

I recommend long Axalta Coating Systems, Ticker AXTA. Stock is at $28 a share, my 5-year target price of $60 per share, implying a 20% IRR through 2020.

Axalta is the $6.5 billion market cap global market leader in OEM and aftermarket automotive coatings. It also makes coatings for industrial applications. The company generates revenue through the manufacturing and selling of coating. It operates in a fairly consolidated industry as one of the market share leaders.

My theses are three fold:

The company's product represents a small portion of customer spending but is mission-critical for auto repair since rework is costly. This creates high barriers to entry and meaningful pricing power. I believe the company's ability to continue raising prices supports an attractive GDP-plus growth algorithm (this thesis impacts revenue)

Axalta has significant exposure to the large MSO (multi-shop operator) space. As the largest MSOs continue to consolidate, Axalta benefits from a natural tailwind to grow market share, which I estimate will drive 50 to 150 bps of annual volume growth (also impacts revenue)

Based on my margin comparison with other paint companies, I believe management is understating the $125 million cost savings projected over the next two years. My calls with former employees suggest Axalta has several low-hanging cost-cutting opportunities, which I conservatively estimate at a minimum of $150 million. (impacts margin, and it’s a variant view)

To summarize, I recommend long AXTA with a $60 target price based on a 18x on my 2020 EPS of $3.20, implying 20% IRR through 2020.

Understanding the business and its industry

You need to understand the business and its industry. What drives its growth? For example, is it:

Penetration story: E-commerce was 2% of retail in this country—now it’s 10% five years later. Where will it be in another five years? What % of that market does this e-commerce company serve? Same goes for all the secular trends (cloud, digital payment, GLP-1 adoption, etc.)

Unit (volume) story: ToadCo opens five stores a year, each generating $500K in sales with $75K in four-wall EBITDA. How many stores will they open going forward? (and how many EBITDA contribution)

Price story: Netflix and Spotify raise prices by X% annually. Can that continue?

Market share: This company has historically gained 100bps of market share through roll-ups. Can that keep going? Easier to argue if the leader only has 10% of the market—harder if they’re already at 70%.

New product/geo/end market: Size the opportunity and the growth pace. Also, check the base rate—if you’re forecasting 10% growth, has that ever happened in this industry? Apple sold X iPhones in Y years—can your company’s product do the same? Why?

Same goes for margins:

Margin story: Who’s the best-run business in this sector? What are they doing differently? Can this CEO pivot the company toward that model?

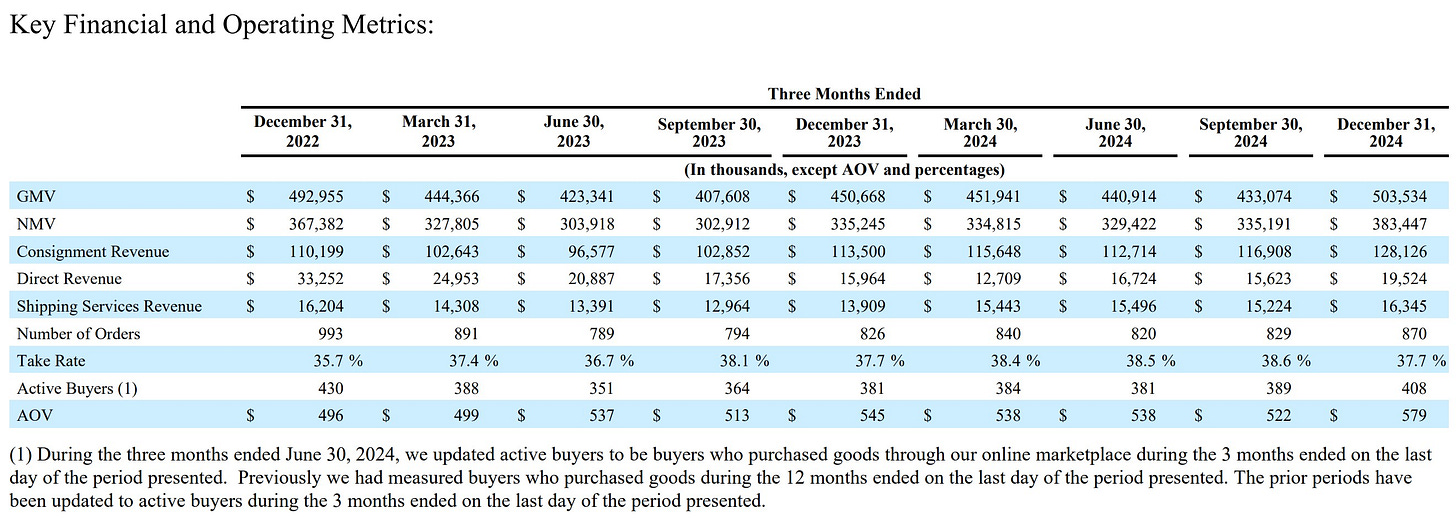

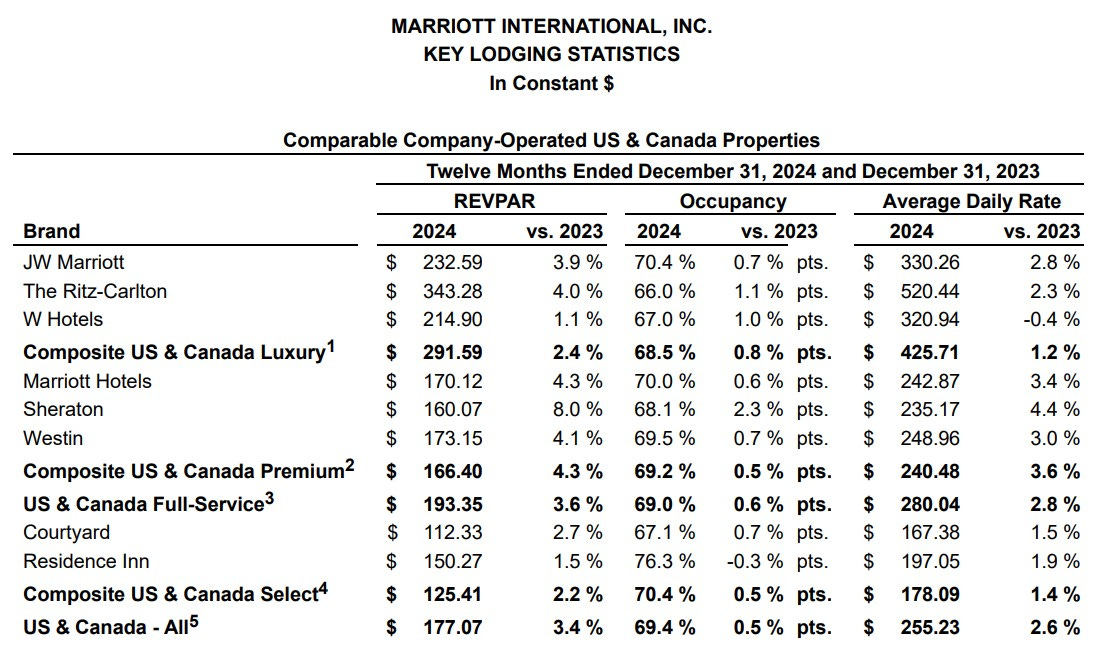

If a company discloses business drivers, your pitch is on auto-rejection if you don’t isolate the drivers in your model and thesis. If your pain point is a research process / modeling / valuation one, I strongly encourage you consider the Analyst Academy.

For examples, companies in various sectors disclose KPIs during earnings release:

E-commerce / payment

Airlines

Hotel

Cable / Subscription Media

Commodities

Some businesses are inherently unpredictable or have too many segments (e.g., megacap multi-industrial companies). You need to decide whether you want to risk your candidacy on such a pitch.

What’s not a thesis

Your theses need to be company specific - why this stock wins over others in the same bucket. The following impact one or more sectors, but not company specific:

Secular trends: Just because an industry is growing (e.g., e-commerce, EVs) doesn’t mean every stock in that space is a good investment. You need to explain why this company has a competitive edge—better unit economics, market share gains, superior execution, etc.

Macro: A rising tide (consumer spending rebound) may lift all boats, but you need to explain why this stock benefits more than its peers. Does it have better margins, pricing power, or customer retention? Otherwise, any consumer stock would do.

Tactical: Betting on investor flows (sector rotations) isn’t a company-specific thesis. Even if your rotation call is right, you haven’t justified why this stock is the best way to play it. Does it have superior fundamentals, valuation upside, or catalysts others don’t?

You are right on secular trends because everyone sees them. But let’s be honest. You probably can’t defend that tactical and macro call anyways.

What is a thesis?

An actionable idea is where you have a differentiated view on the financial outlook of the company and/or the valuation multiple.

Value

If you’re a value investor, you might be playing for an asset sale, liquidation, or an operational turnaround.

Asset sale : Say a company has $100 in assets and $70 in liabilities, meaning a book value of $30. If the stock trades at $9 (30% of book value), an investor could buy a big stake, push for an asset sale, and profit when those assets are sold at a higher price. If they sell for $120, the company gets $120 in cash, pays off $70 in liabilities, and pockets $50. Since the investor bought in at $9, they’ve made $41 per share.

Turnaround or mean reversion: A company that normally grows revenue 5% sees a 20% drop this year—maybe from a lost customer, supply chain issues, or a pandemic. This decline might push its valuation to 12x earnings, while peers trade at 18x. If the business recovers to its usual growth and margin levels, earnings normalize, and the multiple could expand, driving a strong stock price rebound (see what I mean by you will get multiple expansion anyways?)

Growth

If you’re a GARP investor, you’re looking for a company with above-market growth at a reasonable valuation. For example, you’re paying 25-30x earnings and not expect multiple expansion—if EPS grows 20%+ annually, the stock will grow 20%+ as well (but really hard to find).

If you’re a hypergrowth investor, you’re betting on a company with a massive addressable market that isn’t profitable yet but has huge future earnings potential. The idea is that you’re paying a low multiple on the out-year earnings, leading to a great IRR. Philippe Laffont’s Apple example always comes back to the stage in such discussion.

What was misunderstood? The duration of high growth—Apple sustained rapid growth for much longer than expected.

In other hypergrowth examples, the bet is on the high incremental margins—Profit grew much faster than revenue, driving exponential earnings growth and making the original entry multiple look cheap. Visa and Mastercard are prime examples.

Of course, you only know you’re right years later—but that’s the kind of bet Tiger-style funds make.

Sum-of-the-parts (SoTP)

Imagine a $12 billion enterprise value company with two segments:

Consumer products: A market leader in personal care, does $6 billion in revenue with a stable 20% EBITDA margin.

Industrial equipment: Makes construction equipment for a highly cyclical market, with $4 billion in revenue and averages 10% EBITDA margin but volatile.

The overall company has a 7.5x EV/EBITDA multiple (12B / (6B*20%+4B*10%)).

Now, the company announces a split into two to cater to different investor bases.

Pure-play consumer product companies can get a 15x EV/EBITDA multiple, while industrial equipment companies get 7x.

After the split, the consumer product segment should have an EV of $18 billion, and the industrial equipment segment should have an EV of $2.8 billion.

As a shareholder of the combined company, the upside is:

($20.8 billion post-split EV) / ($12 billion pre-split EV) = 73% upside.

My only advice is don’t pitch a SoTP without an imminent catalyst (announced spin-off, activist involvement, asset sale, etc.) that will unlock value. The market tends to value diversified businesses at a lower multiple than their standalone peers.

Don’ts

Don’t pitch mega-caps. They’re heavily covered, making a unique take hard. Plus, with multiple business segments (like Microsoft serving consumers, office workers, and enterprises), analyzing them all is overwhelming, especially when you’re still learning.

Stick to small/mid-caps. They’re easier to analyze, usually with one product and market. I like the $1B–$15B market cap range. It’s not a hard rule—if a $500M or $20B stock is compelling and liquid enough for your audience, go for it.

Don’t pitch stocks owned by the fund. It’s unlikely you know more about a company than someone risking big capital behind the same idea. If you are mandated to pitch a name they already own, it’s what it is.

Content-audience fit don’ts

No technical analysis or macro ideas or arbitrage trades to a fundamental shop.

No shorting pitches to a long-only fund.

No trading-quarter theses to a long-term shop.

No ultra-growth ideas to a value fund and vice versa.

No insider information.

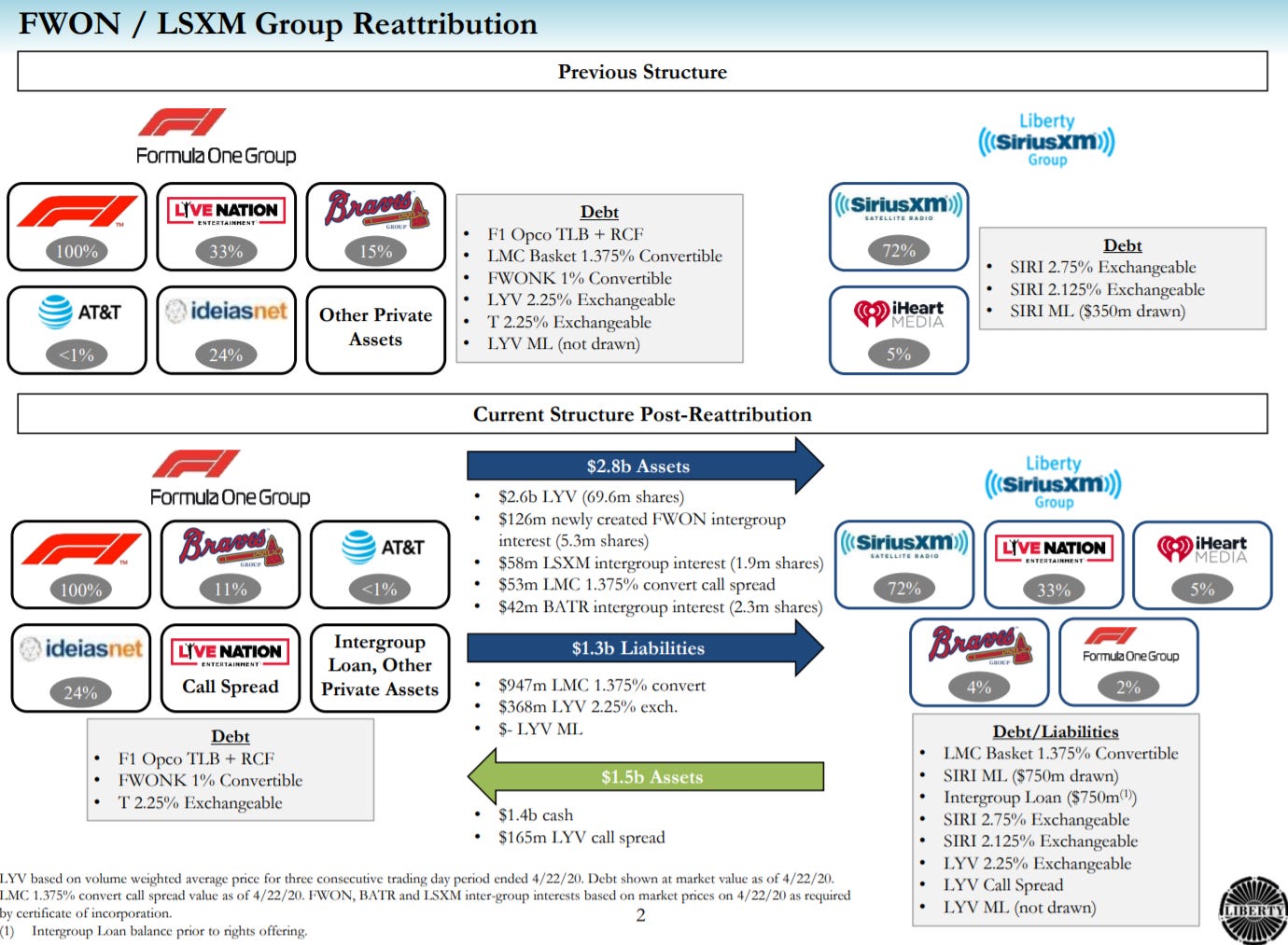

No complex corporate or business structures (e.g., Liberty Media).

No extra alpha in complexity.

Just because Seth Klarman likes playing PG&E after the California wildfires doesn’t mean you have the expertise to form a variant view on a situation like that.

If you don’t have a biotech background, don’t pitch a biotech stock.

Think twice about pitching complex software or semiconductor stocks, as your interviewer might get lost or uninterested if they are not an expert in the sector.

There’s no extra alpha in ESG headwind-ed businesses like cigarette companies, or in uncertain secular trends like crypto or space exploration. All it takes is for your audience to be close-minded, and you won’t get the job.

The goal is to get the job. Even if it’s a money-making idea, you didn’t get the job if you failed to communicate it clearly and/or failed to maximize your addressable audience. The best ideas are simple and understandable.

I’m fine with people pitching borrowed ideas—as long as you do the work to develop the same level of conviction and knowledge as the author. With so many hedge funds sharing ideas publicly, it’s tough to find an idea that hasn’t been mentioned online. Just be careful with heavily discussed names (especially on Twitter). If you really know your stuff and can back it up, you’ll be fine.

Ways to differentiate

If you want to impress, you have to do things others are not doing. Everyone has access to some sets of branded alt data and expert network transcripts.

Here are some ways to differentiate (just a warning - don’t lie about having done these because your audience can call your bluff as they are all professional information gatherers)

Survey (use tools like Survey Monkey and learn how to pose good questions to avoid getting biased answers)

Field work (walk the physical stores, eat 75 Chipotle burrito bowls)

Talk to customers and suppliers / distributors

Talk to IR, talk to ex-executives, talk to people in the industry (I love talking to product managers)

Dig into obscure filings (short sellers at Sohn last year talk about digging into offshore filings that no one reads)

Benchmark studies: margin structure of peers, can the CEO of your company get there? Does the CEO have the levers to pull?

Endless creative ways that I don’t know about, if you care to share!

I hope this helps. Please comment if I missed anything. If you find this useful, please share with your peers who are gunning for investment research.

Thanks for reading. I will talk to you next time.

Resources for your public equity job search.

Check out my other published articles and resources:

📇 Connect with me: Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn | YouTube

If you enjoyed this article, please subscribe and share it with your friends/colleagues. Sharing is what helps us grow! Thank you.

Awesome stuff, thank you so much for sharing! 2 questions: 1) Do you need to have a variant view for each of the thesis (i.e., how your view differs vs. consensus, & how that particular variant thesis drives the valuation)?; 2) Variant view refers to being different vs consensus (in this case defined as market, which is different from the sell-side right?)