Drug dealing, often depicted in popular culture as chaotic and violent, is in reality a structured business with its own supply chains, pricing strategies, and profit margins. Beneath the surface of this illicit trade lies a world driven by basic economic principles: supply and demand, risk management, competition, and innovation.

After reading Narconomics by Tom Wainright, I learned plenty about this multi-billion shadow industry. In this series, we dive deep into the economics of drug dealing, exploring how these black market entrepreneurs operate.

Cocaine’s supply chain

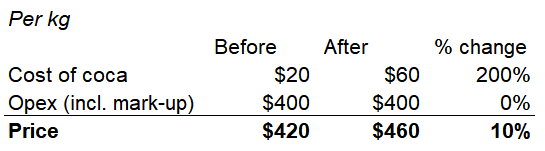

Most coca plants are grown in Bolivia, Colombia, and Peru, where governments are trying to destroy crops. The governments hope that reducing supply will raise cocaine prices and deter demand. Despite these efforts, prices remain stable. To understand why, examine the cocaine production value chain.

Drug cartels don’t grow coca plants themselves; they buy coca leaves from farmers, then process, package, and sell the cocaine. Normally, farmers could sell to the highest bidder, but armed conflicts between cartels mean each region is dominated by one major cartel. This creates a monopsony, where farmers have only one buyer and cartels hold bargaining power.

Despite the increase in production costs, cartels can pay the same amount for coca leaves by squeezing the farmers' margins. As a result, crop eradication strategies end up impacting the wrong people: the farmers rather than the cartels, and ultimately with no net increase to the final price consumers pay for cocaine.

Can there be multiple buyers for coca leaves? No, because cocaine is illegal in most places, governments can't increase the number of buyers in the market. This shows that disrupting production to reduce cocaine consumption has been ineffective. We'll explore other reasons for this failed policy.

Policymakers have suggested encouraging alternative livelihoods for farmers, but this approach has challenges. For example, farmers could switch to planting corn, but corn prices are volatile compared to the steady demand for cocaine. When corn prices dropped in the 1990s, many farmers switched to growing marijuana and opium poppies instead.

The author argues that governments should provide multiple attractive alternatives for farmers. If cartels try to lower prices, farmers could switch to more profitable crops, potentially forcing cartels to pay more for coca leaves. This aligns with the government’s goal of raising the final price of cocaine. However, further issues remain.

For one, cartels have increased cocaine production yields. Colombian cartels can now produce about 60% more cocaine from the same amount of coca leaves than before. In Bolivia, new chemical precursors and machinery have doubled cocaine yields. As a result, reducing coca crops hasn't significantly decreased the overall supply of cocaine.

Most of the cost of cocaine comes from distribution expenses, not raw materials. The high price of cocaine is primarily due to the expenses of secretive global shipping, including bribery and violence—costs that legal businesses don't incur. The more than 30,000% increase from the "farm gate" price of coca leaves to the final retail price illustrates the difficulty of influencing cocaine prices through raw material costs.

Thus, even tripling the cost of raw ingredients would not significantly impact the final price or deter consumption. This is similar to the art market, where the cost of raw materials is minimal compared to the high price of the finished product, which is mainly driven by perception and brand value.

Instead, counternarcotic agencies might have more luck targeting the most valuable part of the cocaine supply chain, closer to the U.S. border, which leads to the next point.

Competition vs. collusion

Violence associated with drug dealing began in South America, especially Colombia, but has since shifted to Central America and more recently to Mexico. Paradoxically, El Salvador, once the murder capital of the world, has seen crime decline, while violence in Mexico has surged. The reason for this lies in the structure of the drug industry.

Collusion, whether among drug cartels or businesses, aims to transform a competitive market into smaller monopolies. For example, if two telephone companies operate nationwide, competition drives prices down and profits lower. However, if they collude to divide the country—one covering the north and the other the south—they can each create a small monopoly, charging higher prices for lower-quality service. While collusion is illegal in legal markets, illegal enterprises like gangs often avoid antitrust laws, making such collusion among rival gangs more common.

Improved conditions in El Salvador are mainly due to a truce between the two major gangs, MS-13 (Mara Salvatrucha) and Barrio 18. The labor market for Salvadoran gang members, or "mareros," is highly illiquid and effectively a duopoly. Once initiated, gang members are heavily tattooed, preventing them from switching to the rival gang. With no other gangs to join and legal employers generally unwilling to hire gang-affiliated individuals, options for gang members are very limited.

The truce, or collusion, worked in El Salvador because the gangs operated locally. By dividing the country into uncontested "sectors," the gangs can charge higher prices for drugs and extortion, reducing the costs of internal conflict.

In response, the Salvadoran government has allocated $72 million to encourage legitimate businesses to hire former gang members, offering a third option. However, these policies and the truce are controversial. While the murder rate has decreased, extortion—primarily affecting civilians—remains unchanged. Despite these challenges, violence in El Salvador has improved.

This strategy doesn’t work for Mexico, where six border states have the highest murder rates due to cartel battles over U.S. drug market access. Post-9/11 border security has increased, making each crossing more valuable. With only forty-seven official crossings along the 2,000-mile U.S.-Mexico border, the major ones handle most shipping traffic, making control of a key crossing crucial for cartel success.

As a result, Mexican border cities like Ciudad Juárez (bordering El Paso, TX) have become battlegrounds for control over crucial U.S. entry points. Intense competition exists between the Sinaloa and Juárez cartels. The Juárez cartel had previously bribed officials and controlled local police, prompting the Sinaloa cartel to launch an aggressive campaign to take over the territory.

In corporate takeovers, businesses must persuade regulators to approve their deals. When GE sought to acquire Honeywell, it got approval from U.S. regulators but faced opposition from competitors who blocked the deal through European regulators.

For cartels, the main regulators are the police, whom they must bribe or intimidate. The Juárez cartel's enforcement arm, La Línea, was made up of loyal former and current police officers, making it difficult for the Sinaloa cartel to sway them. Initially, the Sinaloa cartel resorted to violence, systematically killing local police officers until the remaining force fled the city. When El Chapo (leader of the Sinaloa cartel) couldn't convince Ciudad Juárez's local police to support his takeover, he turned to a different authority for help.

Mexico’s complex policing system created loopholes. With over 2,000 local police forces, thirty-one state forces, and a federal police force operating nationwide, El Chapo saw an opportunity with the federal police. Unlike the city and state police, who were on the Juárez cartel’s payroll, the federally recruited officers (the “federales”) had no local loyalties and were more susceptible to persuasion.

The federales began arriving in Ciudad Juárez, leading to intense confrontations between rival police forces. Slowly, and with considerable bloodshed, El Chapo and his allies gained the upper hand. Once the Juárez cartel's resistance weakened, Sinaloa’s acquisition of the territory was complete.

The takeover didn’t address the broader issue. With only a few key border crossings and ports, and Ciudad Juárez handling about 70% of northbound cocaine traffic, fairly dividing these routes is challenging. While drug distribution in Mexico was once more consolidated under Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo's (former leader of the Guadalajara cartel) plaza system, it is now fragmented. Rival cartels use extreme violence to control territories, creating a winner-take-all mentality and raising operating costs (e.g., bribes, sicarios). This fragmentation drives up cocaine prices, highlighting where most of the cost increase lies.

Policymakers might consider alternative approaches to Mexico’s situation. The intense violence stems from fierce competition for U.S. border crossings. Increasing the number of crossings could reduce their value and make them less contested. Although there are concerns this might boost drug volumes, evidence shows that tightening access hasn’t significantly reduced smuggling. Thus, more crossings could lower violence without greatly impacting the U.S. illegal drug market, creating a dynamic similar to El Salvador, where different cartels distribute their goods across distinct border crossings without clashing.

As Charlie Munger said, "Show me the incentive, and I will show you the outcome." Improving police vetting and increasing officers' wages would also make bribery more costly. Mexican cops are easily bribed because working for the cartels is often more financially lucrative than working in law enforcement. Even Gallardo himself started as a small-town police officer. Streamlining the police system by merging forces could make it harder for cartels to exploit rival police units in their proxy wars.

Cartel recruitment

How Prison Reforms Can Tackle Cartel Recruitment

As we've previously discussed, drug cartels have an opex (operating expense) heavy cost structure. This makes attempts to influence the price of cocaine through the cost of goods largely ineffective. A big portion of opex stems from personnel recruiting to sustain operations. The work is dangerous, resulting in high turnover rates, as sicarios (hitmen) often die, get poached by rival cartels, or end up in prison.

This brings us to a key point: the role of prisons in the cartel cycle. Once in prison, former cartel members can be recruited, trained, and offered jobs for when they're released—often returning to cartel life. Gangs essentially run recruiting operations within prison walls.

Recognizing that prisons are a natural recruiting ground for cartels, some anti-narcotics organizations have begun tackling the issue from the inside. Prisoners are often neglected by society upon release, facing limited job prospects and family rejection. This lack of support frequently drives them back to the cartels, perpetuating the cycle that led to their imprisonment.

Rethinking Prison Design to Reduce Recidivism

Law enforcement agencies are rethinking prison design to disincentivize reoffending and reduce cartels' capacity to recruit from this pool.

For example, prisons in Latin America have historically segregated inmates by gang affiliation into different prisons to prevent inter-gang violence within prison walls. However, this strategy created a new problem: it reinforced gang unity and made recruitment easier within each prison.

Recent efforts in the Dominican Republic involve a new model where maximum-security areas isolate gang leaders, preventing them from directing operations from within. Strict measures, including the confiscation of cell phones from visitors and monitoring of inmates and guards, are in place to communicate with each other and with the outside criminal world.

In a women's prison in Najayo, Dominican Republic, inmates are engaged in productive work, such as making candles, flower arrangements, and jewelry. These items are sold to visitors in a prison gift shop, 70% of the proceeds going to the inmates (who get 30%) and their families (who get 40%). This initiative aims to maintain inmates' connections with their families, as one of the reasons people join gangs is the lack of a support network. Maintaining family ties provides a sense of belonging, reducing the allure of criminal organizations.

Redefining Prison Staffing and Operations

Traditionally, prisons in Latin America have been run by low-performing members of the military or police forces, which often leads to corruption and poor management. Next-generation prisons also require a different staffing approach.

In the Dominican Republic, however, ex-police or military personnel are banned from working in experimental prisons to reduce corruption. Instead, the prison system recruits and trains its staff, offering them salaries three times higher than the old system, making them less susceptible to bribes from cartels.

Moreover, providing meals in-house has eliminated one of the biggest sources of prison contraband: smuggling weapons or drugs hidden in food deliveries. While running new, reformed prisons may be more expensive, it is a cost worth bearing. The taxpayer may not like paying for criminals' lunches, but it is a cheaper alternative than dealing with the aftermath of rampant corruption and violence and paying for metal detectors.

Understanding Cartel Labor Dynamics

Unlike legitimate businesses, drug cartels do not have formal labor agreements binding their "employees" legally. While you might assume cartels automatically resort to extreme violence when dealing with insubordination, the reality is more nuanced. Violence is often a last resort, as losing personnel can be costly for cartels. Interestingly, most traffickers prefer to use nonviolent methods to settle disputes whenever possible, understanding the challenges involved in recruiting and maintaining reliable contacts in the drug trade.

Cartels face significant challenges in managing their labor force. Some prefer to hire many full-time employees. A growing trend among some cartels is adopting a franchise model, working with a network of freelance workers who do not know each other well—reducing the risk of exposure if one member is captured or turned.

A New Approach to Reducing Cartel Recruitment

Many of the issues with cartel recruitment stem from inadequate state approaches that leave inmates vulnerable to the influence of criminal groups that offer them protection and privilege. The more the state fails to meet prisoners' basic needs, the greater the opportunity for criminal gangs to step in and fill the gap. By focusing on improving prison environments and reducing the flow of recruits from within, governments can significantly impact the cartels' ability to replenish their ranks.

In conclusion, the key to reducing the pool of hirable talent for cartels lies in improving the conditions where this talent is sourced—in the prisons. By rethinking prison design, management, and inmate rehabilitation, we can disrupt the cycle of crime and reduce the grip of cartels on vulnerable populations.

Cartels and Their Sales & Marketing Strategies

Even in the legitimate business world, traditional advertising has seen its influence wane, with many companies shifting towards public relations (PR) to shape consumer perceptions. Interestingly, drug cartels have also recognized the power of PR and take it very seriously.

Securing public support—or at the very least, public indifference—is a scalable way for cartels to deter being reported to the authorities. For those who have watched Narcos, you're familiar with Pablo Escobar being revered by Medellín citizens and the Rodríguez brothers of the Cali Cartel investing in local communities, such as building football stadiums and keeping the local economy afloat. These actions are all part of a broader PR strategy.

Cartels often use intimidation to manage their public image by silencing local journalists. This prevents negative news about drug-related violence from spreading, reducing the likelihood of increased law enforcement and allowing cartel operations to continue unimpeded.

The Two Audiences of Cartel Propaganda

Cartels target their propaganda efforts at two main audiences:

The General Public: By convincing people that they are the more "honorable" cartel—claiming not to extort or harm civilians—cartels aim to cultivate a degree of public support or at least tolerance. If the public perceives one cartel as being less brutal or more just than its rivals, they are less likely to provide intelligence to law enforcement against that cartel and may even inform on its rivals.

Law Enforcement and Judicial Authorities: Cartels often launch propaganda campaigns accusing local police or prosecutors of corruption, aiming to erode public trust in these institutions. If the public believes that law enforcement is corrupt, they are less likely to cooperate with them, further insulating the cartels from scrutiny and opposition.

Because cartels make big money, they often step in to provide public goods and services that the state fails to deliver. In doing so, they improve their public image, making civilians more sympathetic to the cartel despite the dangerous and unstable environment they create.

The Cartel as an Enforcer of Informal Agreements

In regions of the world where the rule of law is weak, cartels and other criminal organizations often step in to enforce contracts and agreements that violate free competition—much like the Italian mafia’s historic involvement in labor unions and the trash collection industry. This involvement means that local businesses, which might otherwise oppose cartel activities, find themselves reliant on the cartels to maintain their own shady business agreements and thus having a vested interest in the cartels’ continued existence.

Changing the Narrative: What Can the State Do?

To counter the positive image that cartels often cultivate, the state must step up its own game in providing basic public services. The more effective and reliable the state is in meeting the needs of its citizens, the less opportunity there is for cartels to present themselves as a "responsible" alternative.

To undermine cartels' role in enforcing illegal agreements, the state cannot replicate these activities due to their illegality. However, increased regulatory oversight and globalization have reduced mafia influence. For instance, New York’s garbage industry, once mob-dominated, is now monitored by the Business Integrity Commission, and globalization of commerce has made local crime groups' control more difficult.

Controlling the PR Narrative and Educating the Public

To prevent cartels from controlling the PR narrative, governments should protect journalists with severe penalties for their murder, similar to those for killing police officers. Additionally, wealthy nations should educate the public on the broader impacts of the drug trade, highlighting that buying cocaine indirectly funds violence and murder in countries like Colombia and Mexico.

In conclusion, addressing cartel PR strategies requires a multi-faceted approach. The state must enhance public services, strengthen legal institutions, and expose the true impact of cartel activities. This will reduce the cartels' allure and weaken their influence over both the public and businesses.

Organizational paradigm shift

In the 1990s, Mexican cartels primarily served the Colombian cartels, transporting drugs through Mexico into the United States. However, after a crackdown in Colombia and the deaths of key figures like Pablo Escobar, Mexican cartels gained control over a larger share of the drug trade. They transitioned from following Colombian orders to managing the entire operation—from production to distribution. In recent decades, cartels have shifted operations to Central America due to weaker law enforcement, cheaper labor, and easier influence over police, judges, and businesses.

A notable change in cartel operations has been the move from a centralized approach to a more decentralized, franchise-like model. Mexican cartels, adopting this model similar to McDonald’s, have seen explosive growth over the past two decades.

The Los Zetas cartel, formed by deserters from the Mexican military, exemplifies this structure. Under the franchise model, the Zetas' central command provides franchisees with military training and, in some cases, arms. In return, franchisees contribute a portion of their revenues (akin to royalties in a restaurant franchise) and agree to a "solidarity pact" to support the Zetas in conflicts with rival cartels. Franchisees are responsible for maximizing revenue in their territories, leveraging local knowledge.

In the illegal drug business, self-financed growth is particularly appealing to the franchisor, in this case, the Los Zetas cartel. Los Zetas enforces operational standards across franchisees, much like McDonald’s ensures consistent quality worldwide. This model also explains the cartel's extreme brutality. The Zetas, more than any other Mexican cartel, document their atrocities—such as beheadings and hangings—often sharing visuals to reinforce their brand. Like McDonald’s uses advertising to promote global appeal, Los Zetas instill fear through these violent campaigns.

However, the franchise model has its drawbacks. One major issue is infighting. In the illegal drug trade, courts can’t settle disputes between franchisees and the franchisor, so territorial conflicts are resolved violently. This has led to clashes between factions like Guerreros Unidos, Rojos, and the Independent Cartel of Acapulco.

Another issue is the lack of mobility. Locally based franchises are less agile compared to top-down organized groups like the Sinaloa cartel, which often allows Sinaloa to strike more effectively in Zetas-controlled areas. Additionally, by ceding control to local managers, cartels risk mistakes that damage the entire brand. Los Zetas have suffered from the incompetence of some affiliates, and the franchise model has made it easier for authorities to dismantle these decentralized networks compared to more complex, centrally organized operations.

As cartel structures have evolved, so too have their products, leading to the rise of synthetic drugs.

Product innovation

Synthetic drugs have become a significant problem in New Zealand. The government has tried to address this by banning certain substances, but these bans target specific chemical compositions, making enforcement difficult. Manufacturers simply tweak their formulas to evade the bans, leading to the creation of legal highs with even less concern for safety.

Regulators struggle to keep pace with industries driven by constant innovation. Due to high R&D costs, the synthetic drug market has become highly concentrated, with smaller firms struggling to compete, further complicating regulatory efforts against large, well-funded companies.

In response, the New Zealand government is considering creating an FDA-like entity to approve legal highs. While not ideal, this approach aims to discourage manufacturers from constantly altering their formulas to evade bans and producing dangerous products. The hope is that this regulatory framework will incentivize manufacturers to focus on making existing products safer and less harmful.

E-commerce

Drugs have moved into e-commerce. In a traditional, open market where legal goods are bought and sold, prices are determined by supply and demand. In the illicit drug market, transactions are conducted in secrecy, and there is no transparent price comparison. Buyers are limited to purchasing from dealers they know and trust, and dealers typically only sell to clients who are reliable and discreet. This lack of transparency means that drug markets are far less efficient.

For instance, a consumer might unknowingly pay $200 per gram for poor-quality cocaine from a trusted dealer, while another seller nearby offers higher quality at half the price. Dealers face a similar issue. They may have potential customers willing to pay more for their product but lack an easy way to identify them. The risks associated with advertising illegal products—such as potential arrest—limit their ability to reach a broader audience. Consequently, drug markets operate as network economies where incumbents with established networks dominate. New entrants face high barriers, including lack of connections and potential retaliation from established players.

The advent of online drug markets disrupts this dynamic. On platforms like the Silk Road or Evolution, buyers and sellers can trade freely without being limited to their personal networks. This reduces the advantage of established dealers and lowers barriers to entry for new ones. Online markets also provide better product information with reviews. For instance, thousands of reviews can offer more reliable insights into a product's quality than informal word-of-mouth. Studies have shown that the quality of drugs sold online is relatively high.

However, drug e-commerce has created new challenges for law enforcements. While governments aim to raise drug prices to deter consumption, moving drug sales online tends to lower prices, expanding market and increasing demand. E-commerce also changes the drug distribution value chain. Traditionally, central brokers—well-connected individuals linking wholesalers and retailers—captured significant value from price jumps, such as the increase from $19,500 to $78,000 for cocaine. This centralization made it easier for law enforcement to target and dismantle the value chain. In contrast, removing one or even several online dealers has little impact on the overall supply chain.

Instead, experts argue legalization of the most dangerous drugs seems to be more effective. The case for legal control, rather than relying on prohibition, is driven by the harm these drugs cause.

For example, some European countries have implemented limited legalization, allowing doctors to prescribe regulated amounts of drugs to the most addicted individuals to help them wean off. This approach removes heavy users from the illegal market, reducing the cartel's customer base and making the market less attractive. As demand decreases, the willingness to supply diminishes, further driving down demand. The argument is that such legalization methods can achieve more than prohibition ever could.

Conclusion

Narconomics is a fascinating read that reveals how industries operating in the shadows still follow fundamental economic principles. The author compellingly argues that, given the persistent challenges in eradicating the drug trade, legalization may be the most viable solution. While it would inevitably come with its own set of negative consequences, if it can reduce both demand and human casualties, it may be the only realistic way to address this complex problem.

Thanks for reading. I will talk to you next time.

If you want to advertise in my newsletter, contact me 👇

Resources for your public equity job search:

Research process and financial modeling (10% off using my code in link)

Check out my other published articles and resources:

📇 Connect with me: Instagram | Twitter | YouTube | LinkedIn

If you enjoyed this article, please subscribe and share it with your friends/colleagues. Sharing is what helps us grow! Thank you.