Book Summary - 7 Powers

The Foundations of Business Strategy by Hamilton Helmer

I will discuss the framework for business quality analysis – 7 Powers, invented by Hamilton Helmer who distilled his decades of management consulting experience into a single book.

Competitive strategy is one of the very few things in investing that are so powerful that it CAN be applied to every company you will ever analyze. I always recommend candidates equip themselves with this skill because it really separates you from your peers in compounding your knowledge once you have this framework down.

WATCH this article:

How a Business Creates Value

Before I share how Helmer defines Power, let us understand how a business creates value. Focusing on the first principles without getting into the accounting, a business needs to:

Obtain financing – equity or debt

Use the financing to buy warehouse, real estate, etc. (capital expenditure on long-term assets), and buy inventory, pay employees (working capital needs)

Generate a profit

Uncle Sam takes a cut called tax. (Profit less tax is also known as Net Operating Profit After Tax, because the finance industry loves jargons)

The leftover is free cash flow (shown above). The value of any asset, such as a business, is the present value of future free cash flows it can generate. So, free cash flow is value creation. (The decision on what to do with the free cash flow is called capital allocation, some of you probably are familiar with the concept)

A good business is then one that maximizes free cash flow generation without needing a lot of incremental capital.

To maximize free cash flow, we have the following levers:

Profit: maximize price, minimize cost (profound insight, no?)

Lower capital expenditure

Lower working capital intensity (eg. Apple collects cash from you up front but delays paying suppliers, resulting in negative working capital. Effectively suppliers are providing short-term financing to Apple)

Minimize tax (that’s an advanced topic that we should consult John “Cable Cowboy” Malone)

Definition of Power

Now coming back to the definition: Helmer defines Power as sustained differential returns (on capital) versus competitors, (ie. a good business consistently generates 30% return on invested capital, or ROIC, when its industry peers generate 5%, sustaining a 25% differential ROIC).

Two things to note: 1) Power of a business has to be assessed within the context of industry peers 2) Competition is not static: new entrants can creep up and management can mis-execute.

The duration of excess return against industry peers constitutes power: If a business generates 30% ROIC for one year and then it starts to generate 5% ROIC going forward, the business has no Power.

There are two requirements to Power:

Benefit: Positive impact to free cash flow – I already discussed the levers previously

Barrier: Presence of obstacle(s) that drives the inability or unwillingness of competitors to drive down the profit for the entire industry, because competitions in a low barrier industry will drive everyone’s value creation down to zero.

Without further ado, the 7 powers are:

Scale Economics

Network Economics

Counter Positioning

Switch Costs

Branding

Cornered Resource

Process Power

Scale Economics

Relative scale matters in relation to industry peers. Especially for high fixed cost businesses, the fixed cost can be spread over a larger units produced, resulting in declining total unit cost as business increases in size.

Benefit: Reduced cost (due to spreading fixed cost over a growing unit produced)

Barrier: costly for a new entrant to replicate the fixed cost but have a much higher unit cost due to a smaller sales volume

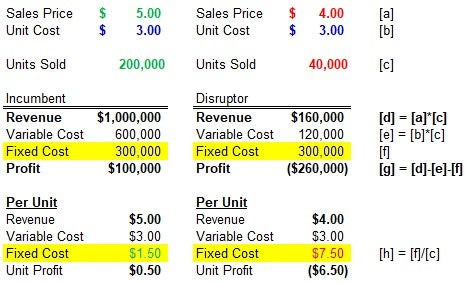

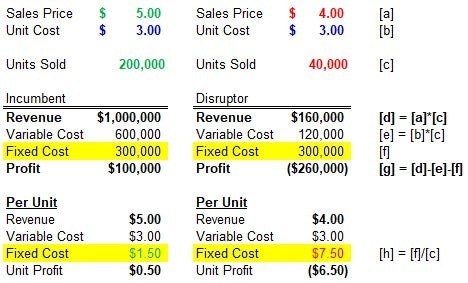

Below is a theoretical example of an entrant attempting to compete with an incumbent who sells 200,000 units a year: The entrant will have to lower its sales price to $4.00 per unit to gain market share. It costs $300,000 to replicate the incumbent’s fixed cost, but its unit fixed cost is much higher at $7.50 (vs $1.50 for the incumbent) assuming the entrant can sell 40,000 units a year as it can only spread the $300,000 fixed cost over 40,000 units when the incumbent can spread the same fixed cost over 200,000 units.

Different types of scale economics discussed in the book:

Volume / area relationships: Milk tanks and warehouses - the cost to make them is tied to surface area since the inside is hollow, but customers pay based on the volume (because that’s how customers measure the value of a milk tank), which is multiples of the surface area.

Distribution network density: Logistics network is high fixed cost. The incumbent built a network that can achieve an acceptable utilization level, resulting in lower delivery cost per trip and better value to customers in delivery time and graphic coverage. It’s very hard for a new entrant when the unit cost is higher since it cannot achieve same delivery volume and the incumbent provides a better product because of scale so customers don’t want to switch (more on Switch Cost in the future).

Learning curve: In a process-driven industry, it takes large amount of units produced and time to get it right and achieve best yield (number of functioning products per batch). It also requires massive capital and the right company culture (I will discuss the latter in Process Power section in a future article). Best example on my mind is Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation, an outsourced semiconductor circuit manufacturing company that commands 40% operating margin (let me know any other outsourced manufacturing company that commands a 40% operating margin, and I will capture it in a jar and study it)

Purchasing power: Classic examples would be Walmart and Costco. These big players are responsible for a big portion of their suppliers’ revenue, so Walmart and Costco can push down on pricing against suppliers and have lower unit cost. Furthermore, Walmart and Costco can pass the benefit to customers. In turn, customers want to come back to them, creating a virtuous cycle.

Network Economics

The proliferation of the Internet destroyed many legacy business models. One of the biggest advantages of internet is there is virtually no incremental cost to serve an incremental user:

Over-the-top (“OTT”) content delivery has no cost to serve an incremental audience.

An online blog platform such as Substack has no cost to serve an incremental reader (more paper is needed to serve another print newspaper reader).

Digital marketplace has no incremental cost to have more inventory since the sellers keep the inventory.

Additionally, the value of the platform increases exponentially for every new user who joins, regardless of whether the platform is one-sided (Whatsapp) or two-sided (Etsy, Airbnb).

Benefit: Leader can charge higher prices because of higher value add (eg. Most supply or demand)

Barrier: Leader has lower unit cost. Being subscale, the entrant has higher unit cost. Additionally, to gain market share, the entrant must charge a lower price because of lower value add. The same example used in the Scale Economics section applies here:

With double hit on revenue and cost for the entrant, the question is: What is the entrant’s capacity to suffer? How accommodating is the capital market to fund its aspiration?

Network economics most prevalently occurs in technology where “winner take all” is the grand prize: one firm achieves critical mass, the other players give up because of benefits and barriers solidified by the leader.

Because of the grand prize, early relative scaling is critical. Unfortunately, in 2022, the capital market is no longer accommodative of such “blitzscaling” mentality, a concept popularized by Reid Hoffman, partner at the VC firm Greylock and founder of LinkedIn.

Counter positioning

Counter positioning occurs where a newcomer offers a superior business model or product and the incumbent does not want to respond because of the fear of damaging its core business. For those who have read Clayton Christensen’s book Innovator’s Dilemma, you are familiar with the incumbent’s fear of antagonizing its proven business model and customer base.

Benefit: New business model is superior because of lower cost and/or higher prices (because of higher value)

Barrier: Incumbent does not respond because it does not deem the disruptor credible or does not want to damage their core business

Counter positioning is not the same as disruptive technologies. A classic example that is both technological disruption and counter positioning is Netflix vs Blockbuster. At the right time in history when broadband was just becoming technologically feasible for wide market adoption, Netflix pioneered the delivery of content over the internet while Blockbuster was skeptic of Netflix’s approach and was too hesitant to give up its steady and dominant brick-and-mortar rental store footprints until it was too late. Technologically, Netflix rendered brick-and-mortar rental store model obsolete and counter positioned Blockbuster to become the largest OTT content provider today.

Switch Cost

Switch cost occurs when customers lose value, monetary or non-monetary, by switching to an alternative vendor for future purchases. Switch cost is Power that only benefits a business if there is future purchase from the customer – upsell or recurring purchase.

Benefit: Vendor can charge higher prices

Barrier: Competitors must compensate customers for switch cost either with money or makes the switch easy

Financial: Fee penalties for breaking multi-year contracts; Damage to sales productivity by switching (eg. Salesforce implementation during peak sales season)

Procedural: Learning curve if switching to a new tool – software companies give products for free to college students for that reasons so that they will advocate for the usage of that product when they go into the workforce

Relational: Loyalty programs of airlines are classic examples

Way to increase switch cost: bundling or upselling

CableCos have perfected the bundle model: They sell “triple play” (pay-TV, broadband and mobile wireless) bundle at a discounted price. If you disconnect one service, discount goes away, creating a disincentive to switch.

SaaS copied the playbook and coined the term “land and expand”: Sell customer one product, develop ancillary products and upsell the same customer to create captivity.

Insurance companies do the same: My father thought about switching car insurance, but realized our home insurance premium will go up if we cancel the car insurance with the same carrier.

Switch cost can be destroyed by big technology shift where all the products within the bundle become obsolete.

Branding

All of us have made purchase decisions based on brands whether we realized or not. The formal definition of branding as a Power is “buyer’s attribution of higher value to an identical offering that arises from historical info about the seller.”

Benefit: pricing power due to

“Affective valance”: Good feeling from using the product. Eg. all luxury goods

“Uncertainty reduction”: Peace of mind associated with a baseline expectation. Eg. McDonalds, Starbucks; Do they sell the best burger and coffee? No, but you know what you are getting regardless of where you are.

Barrier:

Cumulative marketing spend (Eg. Tiffany)

Patent / copyright

Risks to branding:

Going down market: My example would be Michael Kors and Coach. Years ago, they were growing like wild fire in China. Then the wholesalers discounted massively due to market saturation, reducing brand perception. By the time Michael Kors and Coach pivoted to selling in their own boutiques to take back control of brand, it was already too late.

Counterfeit: Tiffany sued Costco / eBay for selling fake goods, hurting the Tiffany brand

Changing customer taste: Nintendo struggled as gaming shifted to adults (but Nintendo is probably doing fine now)

Cornered Resources

Preferential access to coveted assets at attractive financial terms

Benefit: pricing power due to scarcity, and lower unit cost (eg. Mining companies own mines with by-products that can be sold at attractive prices, reducing net cost. Similarly, they can operate in jurisdictions with favorable labor cost)

Barrier:

Patent (to blockbuster drugs)

Property rights to scarce inputs (to talents at Pixar)

5 tests of cornered resources:

Idiosyncratic: If a firm can consistently acquire scarce resources, the acquisition process is instead the scarce resource – not any particular resource that was acquired under the process.

Non-arbitraged: Economics must accrue to the company not to the individuals (eg. Must accrue to Pixar the company, not to the creative talents at Pixar)

Transferable: If the assets (such as talents) are acquired, the assets will add value to the acquirer (eg. Pixar talents continue to add value after Disney acquires them)

Ongoing: It lasts over time

Sufficient: It drives continued differential return (eg. If a key cornered talent goes to a bad company and cannot revive the business, he/she alone wasn’t a cornered resource)

Processing Power

To me, this sounds like operational excellence discussed by Michael Porter (inventor of Porter’s Five Forces) that allows a business to earn durable differential returns.

Benefit: pricing power tied to better product, lower unit costs due to superior process

Barrier: replication takes time (learning curve) and the competitor has to have the right culture, leader and organizational structure in place to succeed in replicating (example in the book: Toyota invited Ford to tour its manufacturing plants, but Ford still could not replicate it.)

Most notable example on my mind would be Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation, TSMC. Typically, outsourced manufacturing service business is a low-margin, scale business. However, TSMC commands 40% operating margin because it’s mission critical in the semiconductor value chain as the one of the very few at-scale fabrication plant business, also known as foundry.

Empirically TSMC provides the highest product yield (a measure of % of a dies on a silicon wafer that is not discarded during the manufacturing process; In the picture below, the wafer is the circle, a die is a square).

Processing power is hard to ascertain. Semiconductor manufacturing is all TSMC does and the company constantly refines its process without worrying about designing chips. Because of highest production quality, TSMC has pricing power. Secondarily, TSMC customers face enormous switch cost because most chip designers (eg. nVidia, AMD, Apple) have no manufacturing capability and the plants are tailor designed in collaboration with semiconductor capital equipment providers (such as ASML) and the chip designers.

Conclusion

This concludes the discussion of all 7 Powers. When an interviewer asked Helmer whether there is an eighth power, he responded he has not seen it yet after decades of experience consulting across all industries. These 7 Powers are exhaustive for all companies that exist today.

Remember to apply the framework to every company you will ever look at and deeply understand what has made these businesses great in the past and whether they can sustain the Powers they display – and the devil is always in the detail and needs to be deep dived on a case-by-case basis.

Also remember businesses don’t stay still. So analysis of Power is never a static exercise.

Thanks for reading. I will talk to you next time.

If you want to advertise in my newsletter, contact me 👇

Resources for your public equity job search:

Research process and financial modeling (10% off using my code in link)

Check out my other published articles and resources:

📇 Connect with me: Instagram | Twitter | YouTube | LinkedIn

If you enjoyed this article, please subscribe and share it with your friends/colleagues. Sharing is what helps us grow! Thank you.

GOAT